Major 18th Century Women Writers:

Anne Finch

Francis Burney

Aphra Behn

By Cassi Jennings

Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea

Anne Kingsmill Finch is considered one of the earliest published women poets in England. She may even be the best women poet in England before the ninetennth century. Anne Kingsmill was born April, 1661. She was the third child of Anne Haslewood and Sir William Kingsmill.Her father died five months after Anne’s birth. Her mother remarried in 1662 to Sir Thomas Ogle, and had Anne’s half-sister Dorothy Ogle.

In 1664, shortly before she died, Anne Haslewood wrote a will which gave all control of the estate to her husband, Sir Thomas Ogle. William Haslewood, the children’s uncle, challenged the will in the Court of Chancery and won, which divided the estate between the children. Anne and Bridget went to live with their grandmother, Bridget, Lady Kingsmill, and their brother, William Kingsmill went to live with his uncle William Haslewood. Anne and Bridget joined their brother after the death of Lady Kingsmill in 1672, until William Haslewood’s death in 1682.

Anne grew up reading the classics, Greek and Roman mythology, the Bible, French (for translation), Italian, drama, history, and poetry. Anne’s family was well-educated and believed education for women was important and necessary. So, the Kingsmill girls received informal education and perhaps even formal education. The Haslewood’s and Kingsmill’s were strong anglicans and devoted supporters of the Stuart royalty. Anne Kingsmill went to St. James Palace to be a Maid of Honour to Mary of Modena.

Anne met Heneage Finch, her future husband, at court. He was a courtier and soldier, four years her senior, who was raised in a family with strong royalist connections. Heneage Finch and Anne were married on May 15, 1684, even though she resisted the idea at first. Their marriage, however, was a lasting and happy marriage. Heneage encouraged and actively supported Anne’s writing, even when social roles and restrictions were so prevalent at the time. In fact, Heneage still noted the anniversary of their wedding in his journal as "Most blessed day."

After marrying, Anne resigned her position on the court, while Heneage retained his place there. Thus, the Heneage’s were still closely involved with court life. In 1688, when Parliament offered the crown of England to William of Orange, oaths of allegiance were required by all clergy and lay persons, including Heneage. Heneage refused because he considered his original oaths lasting and forever binding. Heneage and Anne risked fines, imprisonment, and harassment for their allegiance to the Stuart Kings. They soon moved to the country, where they completely dependent on friends and relatives. In 1690, Heneage was arrested on charges of Jacobitism for attempting to join James II in France.

Anne liked the intellectual stimulation of the ‘Court of Wits’, in spite of their antipathy towards women. Because of the treatment of women poets, Anne kept her early attempts at poetry a secret. While Heneage was in London preparing his case, Anne remained in Kent, where she continued to write through bouts of depression and great anxiety. Her writings from this time reflect are sadder and more ironic that her previous works and encompass political and personal themes. They later moved to Eastwell and lived with the Earl of Winchilsea, Charles Finch. Here, Anne received encouaragement from both her husband and the Earl.Heneage’s support was both emotional and practical; he began compiling her works into an octavo manuscript of 56 of her poems. He wrote the poems out by hand, because Anne’s handwriting was difficult to read.

Many of Anne’s poems from her time at Eastwell reflect her enjoyment and sensitivity to the environment in which she lived. By 1710-1711, Heneage and Anne had moved back to England and acquired a house in London. In London, Anne received a lot of encouragement to print her works under her own name instead of pseudo name. Her admirers and friends included Alexander Pope and Johnathan Swift.

Because of the social and political climate of the time, Anne was of course hesitant about publishing her work. Some of her work had been published anonymously in the form of songs, as early as 1691. "The Spleen," for instance, had been published in 1701 and would become her most famous works of her lifetime: a description of and reflection on depression. "The Introduction" circulated privately with her octavo manuscript for some time. In 1713, however, Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions appeared in print. It included 86 poems, and her second play.

On August 4, 1712, Charles Finch died unexpectedly and without children. Heneage became the Earl of Winchilsea, which made Anne the Countess of Winchilsea. The Finches inherited financial problems and legal battles which would be a source of anxiety and strain for years until the settlement in 1720, in Heneage’s favor. Anne became severely ill in 1715 after battling depression and bad health for many years. Her poems began to reflect religious beliefs and concerns over time.

Some of her major works:

1. Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions: Written by a Lady (1713)

2. The Poems of Anne, Countess of Winchilsea (1903)

3. The Wellesley Manuscript

All information from:

Ockerbloom, Mary Mark. "Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea (1661-1720)." A Celebration of Women Writers. Received 07/19/03.

Where to find more about Anne Finch:

Selected poems of Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea:

http://www.web-books.com/Classics/Poetry/Anthology/Finch/Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea:

http://faculty.goucher.edu/eng211/anne_finch.htmThe Anne Finch Wellesley manuscript poems:

http://js-catalog.cpl.org:60100/MARION/AHM-2829The Norton Anthology of English Literature, pg. 963

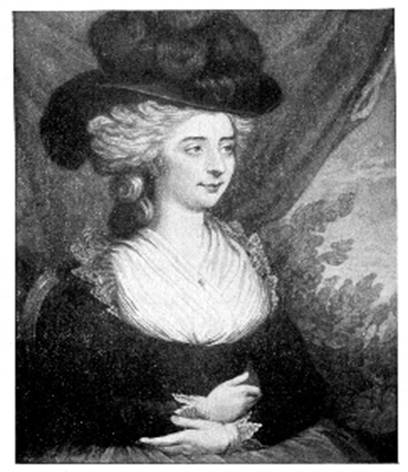

Fanny Burney

Frances Burney was born June 13, 1752 in King’s Lynn England. Fanny’s mother died before she turned ten and left Fanny and her five brothers and sisters and her husband, Dr. Charles Burney behind. Mr. Burney was an accomplished musician, composer, author, and teacher. His reputation allowed the Burney’s to attract the diverse members of the upper-class into their home. These friends of the Burney family became the first subjects of Fanny’s writings. In fact, Mr. Crisp, a close family friend, was the driving force behind the writing and publishing of her work.

Fanny never received a formal education, but her father taught her the skills of writing. Fanny had an unusual talent for memorizing the conversations of other people. Fanny could remember unusual words or phrases a person used as well as their speech patterns. At the age of fifteen, Fanny began to keep a diary and continued to write until she was twenty-five. Her first diary consisted of her journals, her diaries, other people’s behaviors, and letters from Mr. Crisp and her sisters. This collection of her writing was not published until forty nine years after her death in 1889.

Fanny’s first novel, The History of Caroline Evelyn, was burned by her stepmother because she believed novels to be useless materials. However, this book became the basis for her most famous work, Evelina, which was a book of laws and customs for young girls to follow and emulate. This novel was published in 1778. Fanny went on to write many more works which reflected her own social and economic strife. Frances Burney has been said to have began the popularity of the "manners" genre.

Frances Burney did not marry until she was 39 years old, and gave birth to a daughter three years later. Fanny survived the birth of her daughter but underwent a mastectomy in 1811, which she later wrote about explicitly. Fanny Burney was so old-fashioned that she kept her surgery a secret while her husband was away on business so as not to distract him.

Works by Frances Burney:

Fiction:

The History of Caroline Evelyn, destroyed 1767

Evelina: Or The History of A Young Lady’s Entrance into the World, 1778

Cecilia: Or, Memoirs of an Heiress, 1782

Camilla: Or, A Picture of Youth, 1796

The Wanderer: Or, Female Difficulties, 1814

Nonfiction:

Brief Reflections Relative to the French Emigrant Clergy, 1793

Memoirs of Doctor Burney, 1832

Journals and Letters:

The Early Diary of Frances Burney 1768-1778, 1889

The Diary and Letters of Madame D’Arblay, 1904

The Diary of Fanny Burney, 1971

Dr. Johnson & Fanny Burney, 1912

The Journal and Letters of Fanny Burney 1791-1840, 1972-1984

Plays:

The Witlings, 1779

Edwy and Elgiva, 1790

Hubert de Vere, 1788

The Siege of Pevensey, 1788-1791

Elberta, 1788-1791

Love and Fashion, 1799

The Woman Hater, 1800-1801

A Busy Day, 1800-1801

Where to find more information on Frances (Fanny) Burney d’Arblay

: http://dc37.dawsoncollege.qc.ca/burney/biofb.htmlFrances Burney:

http://www.penguinputnam.com/Author/AuthorFrame/0,1020,,00.html?id=1000005928

Aphra Behn (1640-1689)

Born Aphra Johnson in 1640, near Canterbury, England, she was the daughter of an innkeeper; however her parents identities are unknown. Some say Aphra was possibly Eaffry Johnson, who was born to Bartholomew and Elizabeth Johnson.

As the daughter of an innkeeper she was taken to Surinam, West Indies, during the summers as a child. Here is where she met an enslaved Negro prince who would later be the basis for her most famous novel, Oroonoko, or the History of the Royal Slave.

She returned to England between 1658 and 1663 and married a merchant named Behn but she was widowed after only three years of marriage. During this time, Behn was employed as a spy at Antwerp for King Charles II in the war against the Dutch in 1665. She gave naval information and political information to the British government, but was paid very little and not often. On her return to England, she was imprisoned for debt.

After her brief imprisonment, Behn set out to earn a living as a writer. Before Behn, women were forced to publish their poetry or other works under masculine pseudonyms. Most women produced one or two major works and then stopped writing. Women were forced to marry in order to survive; in fact only a few professions were available for women. Aphra Behn is credited with opening the door for women to become professional writers.

Behn’s works include 15 novels (short stories), a book of poetry, translations from Latin and French, and at least 17 plays, many of them comedies. Behn’s works were reactions to the Puritan Commonwealth under Cromwell. Her writings were boisterous and full of sexual innuendos. Behn was accused of plagiarism and of having men help her write her works. These attacks left her with a feminist outlook in that she was aware of the disabilities of women in the World. She was also attacked by her potrayals of human sexuality, even though men were publishing the same types of writings and succeeding financially with those works. After a change in literature, Behn’s work lost favor in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

However later in the twentieth century, women scholars began to look for early female writers and women were more comfortable with discussing sexuality and morality. Behn was not only the first female English writer to write plays, but she also helped to develop the English novel. Her characters were not all feminists, but they were strong characters who viewed life from a woman’s vantage point. She was a Royalist who believed that only breeding and nobility would oppose the commercialism of values she saw on the rise as free enterprise overtook feudalism. Aphra Behn died on April 16, 1689 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Aphra Behn’s Major Works

:Oroonoko, 1688

The Forc’d Marriage; or, the Jealous Bridgegroom, 1670

The Dutch Lover, 1672

The Rover; or, The Credulous Cuckold, 1677

The Counterfeit Bridegroom; or, the Defeated Widow, 1677

The Rover; or, The Banish’d Cavaliers, Part I(1677) & Part II(1681)

The Lucky Chance; or, An Alderman’s Bargain, 1686

The Younger Brother; or, the Amorous Jilt, 1696

Where to find more information on Behn and her works:

The Aphra Behn Society:

The Old Aphra Behn Society Homepage:

http://locutus.ucr.edu/~cathy/behn.htmlBBC’s History of Aphra Behn:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/behn_aphra.shtmlThe Norton Anthology of English Literature, pg. 918

References:

Ockerbloom, Mary Mark. "Anne Finch, Countess of Winchilsea (1661-1720)."

http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/finch/finch-anne.htmlLienhard, John. "No.918: Fanny Burney."

http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi918.htm"Fanny Burney Biography." University of Texas.

http://www.cwrl.utexas.edu/~worp/burney/bio/fannybio.htmlOckerbloom, Mary Mark. "Works by Fanny Burney."

http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/burney/burneyf-bibliography.html"Aphra Behn (1640-1689)." Sunshine for Women.

http://www.pinn.net/~sunshine/whm2001/behn.html"Aphra Behn." Geocities.

http://wwww.geocities.com/Broadway/Alley/5379/AphraBehn.htmlBois, Danuta. "Aphra Behn." Distinguished Women of Past and Present.

http://www.distinguished women. com/biographies/behn.htm"Aphra Behn & the Noble Savage: Oroonoko-Notes and Online Sources."

http://music.acu.edu/www.iawm/pages/african/behn.htmlThe remainder of my sources are scattered throughout my presentation in the "where to find more information" pages.

Thank you for your patience and attention during my presentation!

Note: Text edited from student material by Dr. K. I have not been able to check the printed texts to see if materials were correctly cited but I did edit some obvious typos.