Very few concepts are more important to the understanding of Romanticism than the sublime, the beautiful, and the picturesque. Edmund Burke's definitions in his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful are key. He defines the sublime as a quality of art or experience that "excites the ideas of pain and danger" that produces "the strongest emotion that the mind is capable of feeling" (302) and that causes "astonishment...horror, terror;...the inferior effects are admiration, reverence, and respect." These were the emotions that Romantic poets tried to inspire or recreate in their poems. As Burke points out, the sublime is associated with "greatness of dimension," "infinity," and "difficulty" (305-306) and by things that are rough or rugged. By contrast are things that are beautiful: these things are "small" and inspiring in distress (306). A major component of beauty (in contrast to sublimity) is regularity and control; as Burke says, "I do not now recollect anything beautiful that is not smooth"(306).

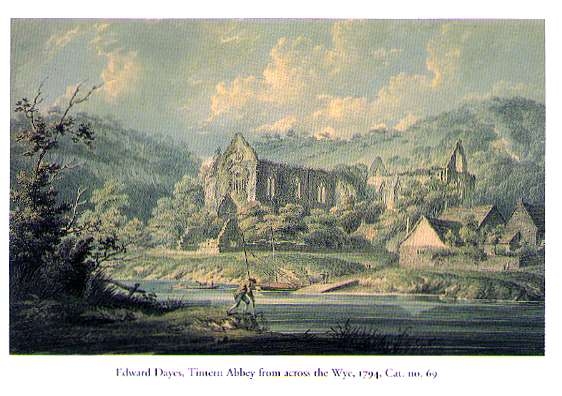

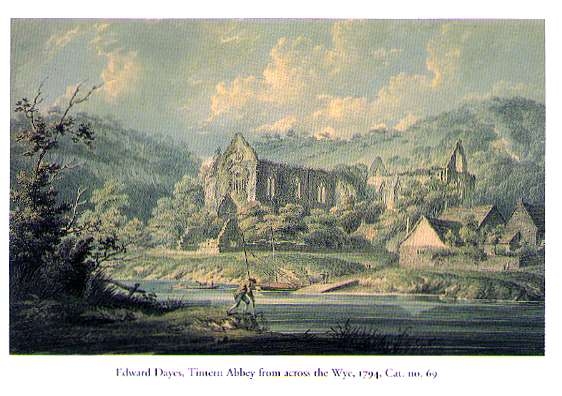

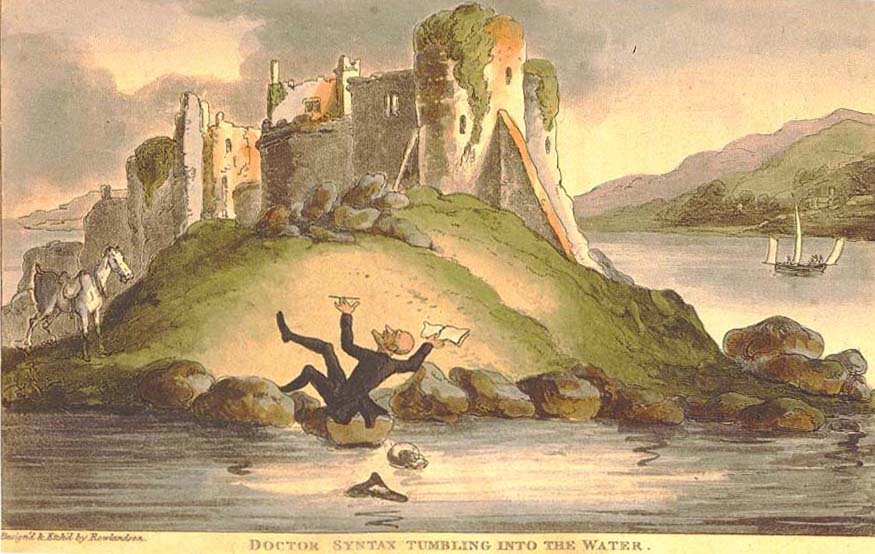

Burke's theories were put into practice by the British painter/critic William Gilpin, whose Essays on Picturesque Beauty, Picturesque Travel, and Sketching Landscape were Romantic best-sellers. He defines the picturesque as objects "which please from some quality capable of being illustrated by painting" (310). He wrote the rules explaining how to paint or sketch a scene in nature to cause the right circumstances for reflecting on it in tranquility; if you compare the Dayes painting of Tintern Abbey (with its aged shepherd, its encircling trees, and its thunderstorm hovering in the distance) and a photograph of the real building, surrounded by modern houses and looking rather bleak, you'll see what he means. It became a great Romantic sport to go look at "picturesque" scenes and be inspired by them (think of Elizabeth's planned trip to the Lakes and to Pemberley in Pride and Prejudice) and thousands of young Englishmen and women found themselves going off to Switzerland or France or Germany to look at Ruins and Think Great Thoughts. (Rowlandson satirizes the "tourist of sensibility" in his Dr Syntax etchings, one of which is in your book and another which is illustrated below.) After Wordsworth and Coleridge moved to the Lake District for its sublime views, it became too touristy for later writers; many of them, such as Shelley, Byron, and Keats, decamped for Italy or Greece for less crowded vistas.

To understand the works of art discussed in this topic, see the good collection of contemporary paintings at http://www.lcc.gatech.edu/~broglio/1102/paintings/paintings.html and the paintings listed at http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/romantic/topic_1/welcome.htm (click on each painting title for a hyperlink to an image).

Painting of Tintern Abbey

The actual ruined church, with the 19th century slums pulled down but the intrusion of modern society shown in the road and the wire-topped fence around the borders.

Rowland, "Dr. Syntax Tumbling into the Water." For more Rowlandson, try this link. http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/rowlandson_thomas.html

Turner, The Passage of St. Gothard. To see more Turner, try this link: http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/turner/ or http://www.artchive.com/artchive/T/turner.html

Title Page of Burke's essay

William Green, "Grasmere" (1815)

Dove Cottage, where Wordsworth lived

Picture

of Derwentwater in the Lake Country

Picture

of Derwentwater in the Lake Country

Looking

up the street from Dove Cottage toward Helm Crag

Looking

up the street from Dove Cottage toward Helm Crag