Key words: Ode, intellect, mutability

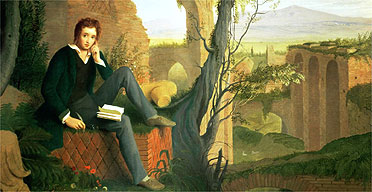

Today Shelley is remembered as a poet of nature and wild raptures; in his day, however, he was viewed as much as a revolutionary and even dangerous political rebel than as a poet. Marx, Engels, and a host of socialist writers in their wake have celebrated his defense of individual liberty. When he was in his mid-teens, he wrote a pamphlet on The Necessity of Atheism that got him expelled from Oxford, persuaded a teenage heiress to elope with him to escape her brutal father, abandoned her for the illegitimate daughter of two freethinking philosophers, and proceeded to establish a counter-culture household in Italy that, while always on the edge of bankruptcy, opened its doors to some of the greatest Romantic artists who ever lived (Keats was on his way to stay with Shelley when he died in Rome). Unlike the "delicate elf" that Victorian critics tried to portray him as, Shelley was a person passionately committed to living out his principles, no matter what the consequences.

Shelley's poetry can be deeply conventional (he and Keats are the two last great masters of the sonnet, a form they were experimenting with at the time of their deaths) and wonderfully irregular: trying to figure out his meter can take days, and there are manuscripts of his drafts of poems where he abandons words entirely and reverts to writing out syllables and stresses ("da da da da da dum") to get the rhythm right.

Shelley sought the Divine in nature, having abandoned his

own faith in a conventional deity; he studied other religions, worshipped the

intellect as the Divine capability in individual men, and saw in nature and in

each act of human emotion an expression of the sublimity he sought.

His "Hymn to Intellectual Beauty" showcases

this search for divinity in the "Spirit of BEAUTY" (p. 397). He recollects his

days as a boy listening for ghosts and seeking terrors as a preliminary seeking

for what he desires, and talks about his devotion to "Awful LOVELINESS" (398) as

a source of inspiration (recollect Burke on the sublime). In his great Ode

to the West Wind he celebrates the emotional sensibility of poets that

is the hallmark of Romantic artistry--calling on the wild West Wind to drive out

the dry leaves of poetic tradition and renew, reshape, reincarnate the poetic

spirit in him:

Be thou, Spirit fierce,

My spirit! Be thou me, impetuous one!

Drive my dead thoughts over the universe,

Like wither’d leaves, to quicken a new birth;

And, by the incantation of this verse,

Scatter, as from an unextinguish’d hearth

Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind!

Be through my lips to unawaken’d earth

The trumpet of a prophecy! O Wind,

If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind? (p. 401)

In this poem, he inadvertently describes the emotional excesses of Romantic poetry in a frequently parodied verse:

O! lift me as a wave, a leaf, a cloud!

I fall upon the thorns of life! I bleed! (401)

The ode "To a Sky-Lark" is even more full of this sensibility:

Hail to thee, blithe Spirit!

Bird thou never wert,

That from Heaven, or near it,

Pourest thy full heart

In profuse strains of unpremeditated art....Like a poet hidden

In the light of thought,

Singing hymns unbidden,

Till the world is wrought

To sympathy with hopes and fears it heeded not: ...Waking or asleep,

Thou of death must deem

Things more true and deep

Than we mortals dream,

Or how could thy notes flow in such a crystal stream?We look before and after,

And pine for what is not:

Our sincerest laughter

With some pain is fraught;

Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.Yet if we could scorn

Hate, and pride, and fear;

If we were things born

Not to shed a tear,

I know not how thy joy we ever should come near.Better than all measures

Of delightful sound,

Better than all treasures

That in books are found,

Thy skill to poet were, thou scorner of the ground!Teach me half the gladness

That thy brain must know,

Such harmonious madness

From my lips would flow

The world should listen then - as I am listening now! (402-04)(The irony here is that he is celebrating "unpremeditated art" in a poem that he reworked many, many times....)

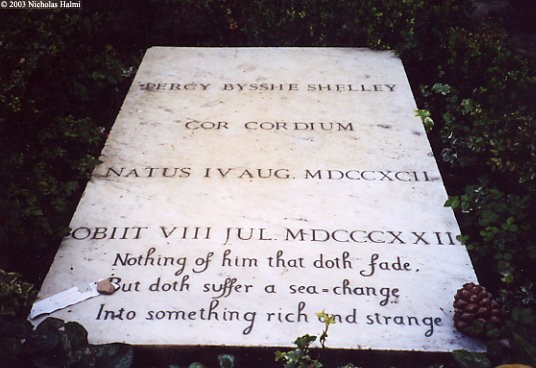

Like so many of the later Romantics, Shelley was impressed with a sense of mutability--the inevitability of change, the knowledge that nothing can be constant, the eroding of belief that anything man-made (whether physical or cultural) can be eternal, and the very human need to believe in something immortal anyway. (The Byron quote on p. 3 of your book is a very concise summation of this feeling.) Shelley's most memorable statement on mutability is in his sonnet Ozymandias (399), where the statue of a ruler who called on his rivals to despair has become worn-down and ruined, buried in the shifting sands of Time.

John Keats (1795-1821)

Key words: lyric poetry, literary criticism, ode, camelion poet, negative capability, egotistical sublime

There are two ways to read Keats--either to be astonished at what he was able to produce in a writing career that lasted a little under four years, or to wonder "what might have been" had he lived, had he taken up the challenge to write drama, had he married Fanny Brawne, had he and Shelley started writing together, etc. The headnote on Keats (421-423) is excellent, so I won't repeat it here; you can take it in yourselves.

Two strains of Keats' work are going to be important to us--first, his lyric poetry and especially his odes. Most of the great ones were written in a spurt between April and September 1819, when Keats, deeply in love with Fanny Brawne, struggling with family illness and the increasing awareness that he himself had contracted tuberculosis, poured out his soul in some of the greatest poems ever written in any language. To this period we owe the Ode to a Nightingale, where the poet's persona wonders if it would be best to die at a moment of ultimate sublime beauty, as a nightingale sings in a moonlit garden: "Darkling I listen; and, for many a time / I have been half in love with easeful Death" (439)--a line made more poignant by the knowledge that Keats had, by this time, nursed his mother and brother through very painful deaths from tuberculosis (consumption) and suspected he suffered from the disease himself. It is also the period of the Ode on a Grecian Urn--Keats' defiant challenge to mutability in a celebration of the art that preserves human culture and emotion--"Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard / Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on" (440) and one of the most perplexing statements of Romantic aesthetic criticism ever written: "Beauty is truth, truth beauty;--that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know" (441). But by the time of the Ode on Melancholy and To Autumn there is a deepening sense that Keats had accepted mutability as a dominant force----"she dwells with Beauty--Beauty that must die" (442) and the beautiful ubi sunt passage that makes up the last stanza of To Autumn.

Keats' last lyric poetry--sonnets like Bright Star and the fragment of drama This living hand--give some sense of where his talents were going. Those who knew him were fairly sure they had a young Shakespeare in their midst. Keats' power of imagery and his control of verse and rhythm make it clear that, had his career developed, the future of British poetry and drama might have changed considerably. Trained as an apothecary (physician's assistant), Keats knew his health was failing and his time was short--the sonnet When I have fears (425), not published till well after his death--show that he knew he would never reach his full potential, and that melancholy awareness permeates all his work.

The other strain of Keats' work to consider closely was his informal literary criticism, usually found in his letters. One of the most important beliefs he espoused was the poet's negative capability--the ability to live "in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason" (445). In other words, the poet has to be able to take himself out of the poem, to refuse the temptation to impose his personality on it to gain closure, to "remain content with half knowledge" (445). He contrasts this with Wordsworth's "egotistical sublime," the need for the poet to put his own experience at the center of everything. The poet's ability to do this, to project himself into various personalities and situations, is what led Keats to name him the camelion [chameleon] poet; the ability to do so is what Keats was experimenting with in This living hand. Keats' letter to Percy Shelley, who had generously invited the younger poet to live with the Shelley household in Italy in hopes that the warmer weather would improve his health, is both a masterpiece of appreciation and also a carefully nuanced statement of the differences between the two poets. Keats tells Shelley to "load every rift of your subject with ore" (448)--an exhortation for Shelley to focus his genius and artistry. (Shelley's elegy for Keats, Adonais, shows what Shelley could do when he took Keats' advice to heart.)

Keats' personal letters, too, are as moving as his poems. His love letters to Fanny Brawne (at least, those which survive; hers to him are buried with Keats) show an impetuous young man in the throes of a passionate first love--sometimes loving, sometimes jealous, sometimes just totally immature--but always readable. And his personal letters of friendship--for instance the last letter to Charles Brown--even when bowdlerized by his editors--show a man who was kind, generous, amused and affectionate--and always worth reading.