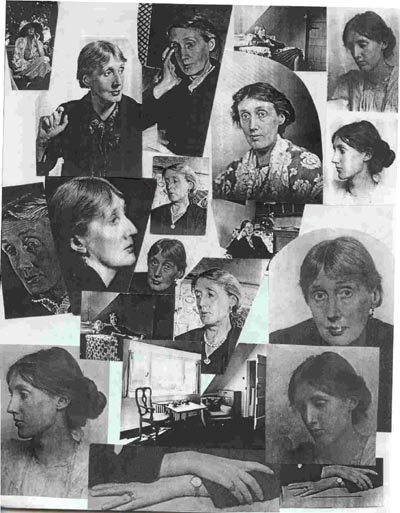

(1882-1941)

very good headnote in textbook

Very much aware of what doors were shut to her as a woman, as someone who could not get a University education (Oxbridge), of the constraints on her sex. Writes from a position that is at once privileged (daughter and wife of literary men who encouraged her writing) and extremely constrained (the "odd" woman, the woman shut out).

Selections from A Room of One’s Own

Her arguments for a decent income and a room of one’s own, literally, as she says in ch.1 of A Room of One’s Own, come from the sense that there is turf she is not allowed to walk on, and that men force her to stick to a confined path. It is a "miraculous glass cabinet" (1231) that she cannot enter into. She creates a picture of history (p. 1232-33) in which men play the leading roles and women are written out of it. It is written with all the loving detail of the naturalistic novelist—you can see that fish, smell those cigars, taste that brandy.

Her picture of what life is like for male scholars at Oxbridge—in the beautiful conditions, with Harry Potter-like banquets and enlightened, stimulating intellectual conditions, is of course partially fiction—but it serves as a striking contrast to the picture "Mary Seton" recounts of the struggles women have had to establish their own schools and places.

Chapter 3: What if Shakespeare had a sister? (p. 1240 ff)

A nice reverse on Gray’s elegy; here she envisions, with some historical inaccuracies, what it would have been like to be an early Modern woman with writing talent, constrained as she would have been by her times. Then recounts how women over time have been discouraged from pursuing artistic careers, from being writers or painters or composers, all by being constrained with "bars of gold."

Chapter 4: The Woman Writer

Women did start to be able to make money by writing. Why did women write novels? Was it class? Were novels easier to hide? Was women’s training more toward the kinds of observations that let her write novels? What if Charlotte Bronte had had more training, more scope, more independence? Women must write what can be read with interruptions

Chapter 6: The Modern Writer

London, leisure to reflect, to absorb, to make sense of the patterns of the city. Are two sexes necessary? Argues for androgyny—the ability to be in touch with both one’s masculine and feminine side.

Conclusion (1251)—"Intellectual freedom depends on material things. Poetry depends on intellectual freedom. And women have always been poor, not for two hundred years merely, but since the beginning of time."

Encourages women to seek their intellectual and material freedom—to seek that room with a lock on the door and the money to pay for it. Make it possible for the next Shakespeare’s sister to come along.

From "Professions for Women"

And while I was writing this review, I discovered that if I were going to review books I should need to do battle with a certain phantom. And the phantom was a woman, and when I came to know her better I called her after the heroine of a famous poem, The Angel in the House.......

It was she used to come between me and my paper when I was writing reviews. It was she who bothered me and wasted my time and so tormented me that at last I killed her. You who come of a younger and happier generation may not have heard of her -- you may not know what I mean by the Angel in the House. I will describe her as shortly as I can. She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there was a draft she sat in it -- in short she was so constituted that she never had a mind or a wish of her own, but preferred to sympathize always with the minds and wishes of others.

......

Above all -- I need not say it -- she was pure. Her purity was supposed to be her chief beauty -- her blushes, her great grace. In those days -- the last of Queen Victoria -- every house had its Angel. And when I came to write I encountered her with the very first words.......

The shadow of her wings fell on my page; I heard the rustling of her skirts in the room. Directly, that is to say, I took my pen in my hand to review that novel by a famous man, she slipped behind me and whispered: "My dear, you are a young woman. You are writing about a book that has been written by a man. Be sympathetic; be tender; flatter, deceive; use all the arts and wiles of our sex. Never let anybody guess that you have a mind of your own. Above all, be pure." And she made as if to guide my pen.......

I now record the one act for which I take some credit to myself, though the credit rightly belongs to some excellent ancestors of mine who left me a certain sum of money--shall we say five hundred pounds a year?--so that it was not necessary for me to depend solely on charm for my living.......

I turned upon her and caught her by the throat. I did my best to kill her. My excuse, if I were to be had up in a court of law, would be that I acted in self-defense. Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing. For, as I found, directly I put pen to paper, you cannot review even a novel without having a mind of your own, without expressing what you think to be the truth about human relations, morality, sex. And all these questions, according to the Angel of the House, cannot be dealt with freely and openly by women; they must charm, they must conciliate, they must--to put it bluntly--tell lies if they are to succeed.1. Why is it significant that Woolf's essay is partly fictional? Why doesn't she write completely in non-fictional mode about the limitations real women face in writing literary works?

2. Consider Woolf's audience. What was the original occasion of "A Room of One's Own"? What kind of audience is she addressing, and to what extent does Woolf do in her essay what she advises other women to do?

3. How does Woolf characterize "Oxbridge" (i.e. Oxford and Cambridge) on 1230 ff. as a material place and in terms of its traditions and conventions? What are the connections between Oxbridge and British life and instutitions beyond the universities?

4. What effects does Oxbridge have on Woolf's semi-autobiographical character Mary Beton? How does Oxbridge limit her and impinge upon her consciousness?

5. From 1234-1236 Woolf analyzes the change in relations between men and women since WWI. How do the Tennyson and Christina Rossetti verses she quotes help her make the points she does? What is it about gender relations that she says has changed since the Great War?

6. From 1236-1240, what does Woolf point out about the difference between male educational institutions (Oxbridge) and women's colleges (Fernham)? What effects does the difference generate?

7. What is Woolf's closing reflection in this first chapter? What does she accomplish by "casting into the hedge" the day's thoughts and occurrences?

1. From 1240-1244, Woolf imagines the career of of Shakespeare's fictional sister, Judith. What happens to Judith, and why? How does Judith's fate show that "genius" is not above history and material circumstance?

2. On 1244, why, according to Woolf, is Shakespeare so little known as a person? What was granted to him that would not have been granted to a sister with equal potential?

1. From 1244-1248, how does Woolf trace the history of women's writing from the eighteenth century onwards? Why was the novel the main genre for female writers in that period?

2. From 1245-47 what contrast between Jane Austen / Emily Bronte and Charlotte Bronte does Woolf make? What limitations did Austin and Emily Bronte reject that Charlotte Bronte was unable to reject?

1. From 1249-50, what, according to Woolf, did Coleridge mean by his term "androgyny"? Why is Shakespeare an excellent example of this quality?

2. From 1250 ff., why is it "fatal" to write solely as a man or as a woman? Why, according to Woolf, is the modern (post-WWI) way of constantly theorizing about gender and gender relations misguided?

3. What exhortation does Woolf offer women in her audience from 1251 on? What does she suggest that women should do to make progress? Is Woolf offering this advice to "women in general," or is her advice offered to a more limited group than that? Explain.