Milton, Adam, & Eve

[Jump to a list of key passages and questions]

Milton’s portrayal of Eve has come under more and more scrutiny as literary criticism has expanded to admit multiple perspectives. Feminist criticism is the name given to the school of literary criticism which examines the ways in which a male culture writes—that is, inscribes, records, establishes the norms for—women. It looks at how power is given or withheld from women and what the effects of that empowerment (or lack of empowerment) are. What follows is a very feminist reading of Milton’s interpretation of Eve; you should be aware that there are other interpretations by well-respected Milton scholars (for instance, Joseph Wittreich), who claim that Milton was a proto-feminist (like Chaucer) because of the honesty with which he portrays this major female character.

Okay, to start with, Milton was a man of his time, the Early Modern Period. His purpose is to ‘justify the ways of God to men;’ women don’t enter into it. The Puritans subscribed even more strongly, probably, than did most of their peers to the kinds of positions on women we read in Vives. In book 7.529 ff, Raphael tells Adam that God "Male …created thee, but thy consort female for race"—race here is the first usage in English of the word to mean reproduction or breeding.

One of the most frequently cited Bible passages the Puritans used to justify

their views on women, and especially on educating women, is this one:

Let a woman learn in silence with all submissiveness. I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent.---1 Tim. 2: 11-12

For Milton and the Puritans, a woman’s obedience to men—to her father, her guardian, or her husband—was a model of the Christian’s obedience to God. It was a moral and religious duty as well as a political and economic reality. Women who disobeyed—who tried to exert self-governance (remember the Wife of Bath’s maistrie?)—were seen as sinners, as rebels against the established divine moral order. When a wife disobeyed her husband—that is, tried to exercise sovereintee—she attacked everything that Puritans believed Christian men should stand for. Milton reflects this attitude in his divorce polemics:

Who can be ignorant that woman was created for man, and not man for woman; and that a husband may be injur'd as insufferably in marriage as a wife. What an injury is it after wedlock not to be belov'd, what to be slighted, what to be contended with in point of house-rule who shall be the head, not for any parity of wisdome (for that were something reasonable) but out of a female pride. --Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce, 2nd ed. (1644)

Milton portrays in Eve the flaws he believes are inherent in all women—the weaknesses that lead them to sin and to cause the downfall of the men seduced by their beauty. First of all, Milton believes that women are narcissistic, obsessed by their own beauty. Only when women are corrected by men can they see that they should be admiring virtue in others, not beauty in themselves. When Eve describes her creation to Adam, she expresses that view:

Eve: A shape within the watery gleam appeared,

Bending to look on me: I started back,

It started back; but pleased I soon returned,

Pleased it returned as soon with answering looks

Of sympathy and love: There I had fixed

Mine eyes till now, and pined with vain desire,

Had not a voice thus warned me; 'What thou seest,

'What there thou seest, fair Creature, is thyself;

'With thee it came and goes: but follow me,

'And I will bring thee where no shadow stays

'Thy coming, and thy soft embraces, he

'Whose image thou art; him thou shalt enjoy

'Inseparably thine, to him shalt bear

'Multitudes like thyself, and thence be called

'Mother of human race.' What could I do,

But follow straight, invisibly thus led?

Till I espied thee, fair indeed and tall,

Under a platane; yet methought less fair,

Less winning soft, less amiably mild,

Than that smooth watery image: Back I turned;

Thou following cryedst aloud, 'Return, fair Eve;

'Whom flyest thou? whom thou flyest, of him thou art,

'His flesh, his bone; to give thee being I lent

'Out of my side to thee, nearest my heart,

'Substantial life, to have thee by my side

'Henceforth an individual solace dear;

'Part of my soul I seek thee, and thee claim

'My other half:' With that thy gentle hand

Seised mine: I yielded; and from that time see

How beauty is excelled by manly grace,

And wisdom, which alone is truly fair.

PL 4. 461-91 (pp. 978-79)

This stubbornness and self-absorption, in Milton’s view, is partially due to the weakness of a woman’s mind. She is by nature, Milton believes, lazy, unfit for study, and unsuited to understand the subtleties of masculine philosophical conversation; it’s better for her husband or father to tell her what she should know, and if she is obedient and biddable, she should believe him. Milton in the divorce polemics snidely remarks that

Who knows not that the bashful muteness of a virgin may oft-times hide all the unliveliness and natural sloth which is really unfit for conversation.

---Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce.

Thus in the four central books of Paradise Lost (books 5-8), it is Adam who eagerly accepts instruction from Raphael and questions him about divine purpose, while Eve wanders about in the Garden picking fruit and flowers and serving lunch. (Since they are this point innocent of sin, both are naked and unconscious of it [5. 443-48], but her nakedness endangers Adam. More on that in a minute.) She blithely announces that she will wait for Adam to tell her what she needs to know—at once a model of her obedience but also evidence for Milton’s argument that a woman’s brain does not naturally seek intellectual stimulation but avoids it. In terms of the plot, it also ensures that she is not present when, in Book 8, Raphael warns Adam of Satan’s plot to corrupt humanity.

Milton also argues that women’s physical attractiveness to men is a flaw, because it makes men forget their natural superiority to women and want to surrender to them. When Adam expresses this attitude, Raphael sternly rebukes him:

Adam: Straight toward Heaven my wondering eyes I turned,

And gazed a while the ample sky; till, raised

By quick instinctive motion, up I sprung,

As thitherward endeavouring…

But who I was, or where, or from what cause,

Knew not; to speak I tried, and forthwith spake;

My tongue obeyed, and readily could name

Whate'er I saw.(skipping over Adam’s account of the creation of Eve)

here passion first I felt,

Commotion strange! in all enjoyments else

Superiour and unmoved; here only weak

Against the charm of Beauty's powerful glance.

Or Nature failed in me, and left some part

Not proof enough such object to sustain;

Or, from my side subducting, took perhaps

More than enough; at least on her bestowed

Too much of ornament, in outward show

Elaborate, of inward less exact.

For well I understand in the prime end

Of Nature her the inferiour, in the mind

And inward faculties, which most excel;

In outward also her resembling less

His image who made both, and less expressing

The character of that dominion given

O'er other creatures: Yet when I approach

Her loveliness, so absolute she seems

And in herself complete, so well to know

Her own, that what she wills to do or say,

Seems wisest, virtuousest, discreetest, best:

All higher knowledge in her presence falls

Degraded; Wisdom in discourse with her

Loses discountenanced, and like Folly shows;

Authority and Reason on her wait,

As one intended first, not after made

Occasionally; and, to consummate all,

Greatness of mind and Nobleness their seat

Build in her loveliest, and create an awe

About her, as a guard angelick placed.

To whom the Angel with contracted brow.

Accuse not Nature, she hath done her part;

Do thou but thine; and be not diffident

Of Wisdom; she deserts thee not, if thou

Dismiss not her, when most thou needest her nigh,

By attributing overmuch to things

Less excellent, as thou thyself perceivest.

For, what admirest thou, what transports thee so,

An outside? fair, no doubt, and worthy well

Thy cherishing, thy honouring, and thy love;

Not thy subjection: Weigh with her thyself;

Then value: Oft-times nothing profits more

Than self-esteem, grounded on just and right

Well managed; of that skill the more thou knowest,

The more she will acknowledge thee her head,

And to realities yield all her shows.

PL 8: 257-575

Above all, Milton argues, women are stubborn and refuse to be governed by men, showing their ignorance, their sinfulness, and their general unworthiness. The debate on working separately in book IX, where we see Eve being politely but stubbornly unwilling to respond to Adam’s guidance (that line about “sweet austere composure” line 272 is a classic), shows this weakness that Milton thought was common to all women. The adjectives in this speech—for instance, “domestic Adam” and “reply with accent sweet renewed”—are wonderful examples of a polite but bloody fight over women’s attempt to claim free will and self-governance. In the debate in Book 9 (ll.205 ff.--beginning on p. 992), Eve’s insistence on working alone, her refusal to be governed by Adam’s ‘reasonableness,’ is an emblem of that stubbornness. And it leads her, of course, directly into temptation. As Milton argues in The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce,

Custom. . . rests not in her unaccomplishment, until by secret inclination, shee accorporat her selfe with error, who being a blind and Serpentine body without a head, willingly accepts what he wants, and supplies what her incompleteness went seeking.---Ibid.

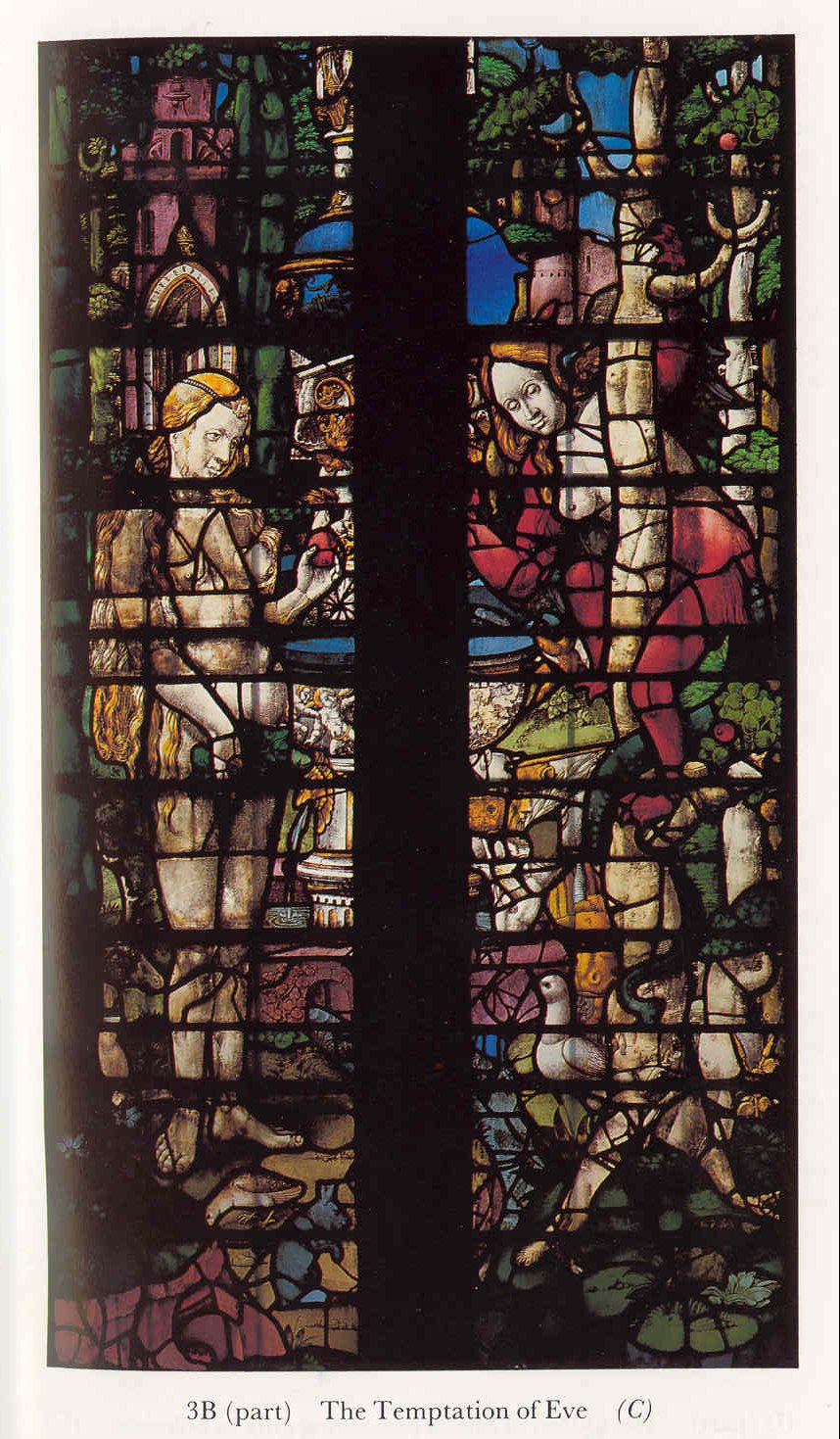

This equation of Eve with the serpent is common in early Modern iconography; in fact, a great stained glass window in the chapel of King’s College, Cambridge (Milton’s college), shows Eve with the serpent, who has her body and her hair, only slightly debased. (See the image at the top of this page.)

Thus, in Milton’s calculus, the Fall of Man is brought about by woman—by her stubbornness, vanity, willing ignorance, and refusal to accept the reasonable guidance of men. The fall takes place in Book 9:781-82 (p. 1004), the only rhymed couplet in the poem; and it clearly is instigated by women. Note that when Satan tempts her, he tempts her not with wealth or flattery, but with equality of status—book 9:882, "equal joy and equal love (p. 1006)." He offers her knowledge—in other words, the intellectual status of being a man—and she, in her ignorance, believes that such is possible under Milton’s divine order. (Remember this is Milton’s position here.) Her actions cause Adam to cry out, in the most bitter rebuke in the poem, against God’s reasons for creating women in the first place:

Adam: O! why did God,

Creator wise, that peopled highest Heaven

With Spirits masculine, create at last

This novelty on earth, this fair defect

Of nature, and not fill the world at once

With Men, as Angels, without feminine;

Or find some other way to generate

Mankind?

PL 10.888-95

One of the most significant issues for feminist critics in the poem is the issue of redemption—is Eve saved? Perhaps, but only by making herself totally submissive to male authority, both God’s and Adam’s. It takes the Fall to make her realize that she cannot outthink men and should not try to act alone; see Book 10:909 ff. She spends most of the last three books of the poem in submissive positions—either on her knees or prone (asleep). In Book 12, when Michael announces the promise of the coming of the Savior (called the Protevangelium in Milton’s time), Adam is grateful—but Eve is asleep (12. 594 ff). Thus, once again her chance to hear divine wisdom passes her by—she must depend on her husband to interpret it for her.

In Milton’s complex theology, both men and women bear guilt for the Fall—but woman’s guilt is greater, not only because she sinned first, but because she uses her female wiles to get man to sin as well. Man’s sin is less than woman’s because she ate the apple for power and greed, while he ate for love of her.

It isn’t hard in a feminist interpretation to see Milton’s larger political purposes here. Britannia, the realm, is personified as female; she is beautiful but susceptible to the temptation by a wicked demon (the restored Charles II). Only if she submits herself to the governance of a morally enlightened man (the Puritan movement) can she remain sinless. Milton’s poem forecasts his hopes that England will realize the mistake she made in returning to monarchic government and return to the wisdom of the Puritan commonwealth. His hopes, however, have yet to be realized.

Key Passages on Gender in Paradise Lost

1. What Milton=s culture says about women: I 26, IV 295-311; IV 635 ff; V 443-48; VII 529

How does this agree or disagree with the perspectives on self-government you=ve read?

2. Milton accuses women of being

a. narcissistic: IV 461-91, V 443

b. too simple for complex theology and too lazy to develop the mental discipline to study it: Doctrine and Discipline quote 2, V 443-48, VIII 40, 49-56 esp.

c. too seductive to men: IV 496 ff, VIII 452-575 (esp. 530 ff); IX 734

d. too stubborn to be guided by all-knowing men: IV 522 ff (the desire to know what is not for humans, esp. women, to know); IX 205 ff, esp. 761; Doctrine and Discipline ;

(see Adam=s speech in X 867-908 in which he denounces the faults of women.)

3. Therefore the Fall happens because woman=s faults, her vanity, and her inability to detect the fallacies in complex arguments lead her to make the wrong choice when exercising free will:

IX 738 ff, IX 524 ff, IX 856 ff (esp. 882 ff). Note especially the couplet IX 781-82.

4. Is Eve redeemed? Only through making herself totally submissive to male authority by doing what she is supposed to in the first place. Most of Books X and later she spends on her knees. Cp. X 909 ff, esp. X 930. Eve realizes that women can=t outthink men.

5. Therefore, who=s to blame for the fall? Eve, because she eats the appleBand then uses her female wiles to get innocent Adam to eat, too. Man=s sin is less serious than woman=s, because she eats for power and greed, while he eats for love. Moral is that women, because they are essentially irrational creatures, governed by vanity and emotion, are not fit to rule or to judge or to act independently; men, essentially rational creatures informed by God, are to interpret the world for women and to act for them. In Milton=s time (and legally up into the 20th century), women had little independent legal existence; they were chattels of menBeither of their fathers or guardians, or of their husbands. Only widows had a tenuous independence, and they were pressured to remarry as soon as possible. To this day, courts cannot force a woman to testify against her husband, because legally the two are one entity, and a woman testifying against her husband is considered to be self-incrimination, and therefore a violation of the accused man=s constitutional rights.