John Milton

John Milton John Milton

John MiltonKey Terms: Puritan, Cavalier, Commonwealth, Cromwell, censorship, prose treatise, art epic

Milton can be one of the most trying but is also one of the most rewarding Early Modern authors to read. Born in 1608, he was the son of a wealthy merchant who hoped his son would become a civil servant or cleric. Young Milton excelled at school, and, after getting expelled for impudence on his first enrollment, finally got his master’s at Cambridge. After graduating, he went home for six years and read extensively, occasionally trying a stint at tutoring but always returning home to the library. Finally, at age 30, his exasperated father sent him to Europe on the Grand Tour. After a year he came back and plunged himself into radical Puritan politics, writing the occasional poem. Somewhere by this point, probably while in Italy, he read Dante and Bocaccio, and like Chaucer, found in their works the challenge to create inspired English poetry.

In May 1642 Milton’s family arranged a marriage with a 17-year old Royalist girl, Mary Powell, whose family had a title and could help Milton’s career. Within 3 weeks the bride moved back home to her family and Milton started writing polemics agitating for legalized divorce. (Her family forced her to return to him in 1645 when their family’s political situation got parlous; she bore him three daughters before dying in 1652.) He also wrote widely (mostly in Latin) against Charles I and in support of Oliver Cromwell. When Cromwell took over the Commonwealth in 1649, Milton became his Latin (private) secretary for the Council of State—Cromwell’s closest confidant. He also went blind; see "When I Consider How My Light Is Spent," p. 910.

In 1656, Milton marries the Puritan Elizabeth Woodcock; she dies in childbirth (along with their son) in 1658. Woodcock is the subject of the sonnet "Methought I Saw My Late Espoused Saint" (p. 910).

In 1660, after the Restoration of Charles II, Milton was jailed and faced execution as a suspected "traitor and purveyor of sedition." He was freed thanks to the efforts of his admirer, the Royalist poet Andrew Marvell, but lost most of his (actually his first wife’s) estate in fines. He retired to a cottage in the country and married Elizabeth Minshull in 1663; she and his three daughters spent their days caring for him and reading to him, phonetically, in four ancient languages. In 1667 came the first edition of Paradise Lost; in 1671, Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes. Milton died in 1674, shortly after the publication of the full (12-book) edition of Paradise Lost.

Works

You Need to Know

Works

You Need to Know

1. Sonnets. Milton’s sonnets are a fusion of the personal and the political. They can be revealingly intimate, as in the mourning sonnet for Elizabeth Woodcock or "When I Consider How My Light is Spent;" or they can be polemical diatribes like "To the Lord General Cromwell" or "On the Late Massacre in Piedmont." Petrarchan in form, they are utterly Miltonic in enjambment, diction, and above all, attitude.

2. Areopagitica. In 1644 Charles I’s government, increasingly worried about Puritan polemic, passed a law that all works published had to receive a government license (imprimatur) before being printed. The effect of this law was censorship—the government would license only those works that supported their positions and beliefs. Milton, in an act of incredible daring, paid a printer to publish his attack on censorship unlicensed—and put his name on the title page, taking credit for the act. The resultant paean to free speech is still used in US Supreme Court cases in defense of the First Amendment (see Vincent Blasi's wonderful 1995 Yale Law lecture for a summary of Milton’s value today). The parts you should know are pp. 911 to the asterisks on p. 912 and the last paragraph of the selection on p. 920. The key passage is the paragraph on p. 911 beginning "As therefore the state of man is now" and the most famous quotation is "I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue….".

3. The Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce

Prior to the Reformation, divorce in England was governed by church or "canon" law. Marriage was defined as a lifelong and sacred union that could only be dissolved by the death of one of the spouses. This view of marriage conceived of husband and wife as made "one flesh" by the act of God; thus marriage was changed from a terminable civil contract under the old Roman law to a sacrament, a humanly indivisible union of souls and bodies.(with thanks to the Milton Pages at www.brysons.net/miltonweb/ defense1.html for some of these notes)

The Reformation denied that marriage was a sacrament; therefore, divorce with the right to re-marry was reinstated. Most Protestant states allowed re-marriage for the innocent party after divorce for adultery. This position was strongly supported in England, since it was the right to divorce that was at the heart of Henry VII's formation of the Anglican Church. However, divorce with the right to re-marry had no solid foundation in Canon law, and in 1597 the Anglican Convocation declared that there was no legal basis for re-marriage after divorce. While Elizabeth I did not sanction the Canons of 1597, the judgment concerning divorce was repeated in those of 1604, which James I approved.

Puritans resisted this position on divorce; many Puritan ministers presided over re-marriages of the innocent parties in divorce for adultery. Milton, however, went much further than that in his demands. In demanding the right of absolute divorce for both parties to any marriage, he extended the grounds to include incompatibility; he also sought to remove divorce from public jurisdiction, and return it to private hands. In the Divorce Tracts Milton argues that the sole cause allowed for divorce—adultery—is less substantial than incompatibility and that being forced to remain for life in an unhappy marriage was an offense against the dignity of God’s creation. (For his pains, he was promptly attacked as a libertine by both royalists and Presbyterians. )

Note that Milton's position is not a support of women--he sees them consistently as intellectually and spiritually inferior to men. Woman is by nature, Milton believes, lazy, unfit for study, and unsuited to understand the subtleties of masculine philosophical conversation; it’s better for her husband or father to tell her what she should know, and if she is obedient and biddable, she should believe him. Milton snidely remarks that "Who knows not that the bashful muteness of a virgin may oft-times hide all the unliveliness and natural sloth which is really unfit for conversation" (see text). He is conventionally Puritan in his attitude to women; despite what some scholars argue, Milton is not a feminist!

Above all he opposes a woman's right to wield power or make her own decisions--he would have hated the Wife of Bath. In The Doctrine and Discipline he argues,

Who can be ignorant that woman was created for man, and not man for woman; and that a husband may be injur'd as insufferably in marriage as a wife. What an injury is it after wedlock not to be belov'd, what to be slighted, what to be contended with in point of house-rule who shall be the head, not for any parity of wisdome (for that were something reasonable) but out of a female pride.

So Milton would side with Vives (758 ff.) that women were still less than men, less than human, and therefore prone to fall.

4. Paradise Lost. Epic poems get their names from their attempt to tell the story of an epoch—a significant time, a significant place, significant characters. In focusing on one story, the epic poet wants us to thing about all stories—all great levels, times, characters, histories. Milton in his youth considered writing an epic to end all epics. He at first thought about writing about King Arthur and his wars, as the ultimate British epic, but eventually decided that the only subject worth his abilities, scope, and time was the greatest epic of all—the War in Heaven that led Satan to be cast out and, in turn, corrupt Adam and Eve. While Milton apparently worked on bits and pieces of it (mostly Satan’s speeches in Bks. I & II) in the 1640s and 1650s, it wasn’t until his bitter retirement after the restoration that he completed the work (1st edition 1667), then expanded it to the form we know now, the 12-book epic published in 1674.

The story is familiar: Lucifer, swollen with pride, rebels against God and is expelled, with his supporters, from Heaven. In the meantime God creates earth and implants Adam and Eve to begin peopling it. Satan in revenge tempts Eve, who causes Adam to fall also, and they are expelled from the Garden of Eden. God promises that his Son will come to redeem their descendents in appropriate time. Unlike Beowulf, this is not folk epic but art epic--consciously 'artificial' and allusive.

Milton, of course, expands the story greatly. Paradise Lost is, really, the last great epic poem (Tennyson tried, but didn’t outdo Milton, and nobody really has equaled his efforts since.) Paradise Lost is therefore significant on a number of levels:a. Epic Level. This is an epic poem in scope and sweep; it is full of the devices we connect with epic: in medias res opening, epic similes, catalogs, invocations, stories of wayfaring and warfaring.

b. Dramatic Level. The Puritans had closed the theatres for spreading immorality, so "closet" drama was all poets could write. (There is some evidence that Milton had at one time intended to write a play on the Fall of the Rebel Angels.) Milton’s poem is splendid blank verse, full of soliloquies and colloquies, and great "set" pieces (such as the devils rising from the sea of Hell and exploring their new lands). The poem is so rich in allusion and metaphor that it literally cannot be read without footnotes; when one realizes that Milton incorporated this heavy level of detail without being able to see his books, it’s really amazing.

c. Theological Level. Paradise Lost is the ultimate Early Modern confrontation of faith and reason; Milton’s announced purpose is "to justify the ways of God to man," as if God is not capable of doing the job but the Puritan poet was. The poem is about the importance of perfect obedience, about the dangers of rebellion, about the possibilities for redemption if one submits oneself totally to the Divine Yoke.

d. Poetic Level. Paradise Lost is a triumph of literary style. No poet in the English language has ever been more skilled with enjambment (look at the length of the first sentence of the poem if you want proof). The poem is beautifully structured, with parallelism, repetition, and foreshadowing. Events mirror each other. It is, in many ways, a textbook for how to write an epic poem—which Milton obviously intended.

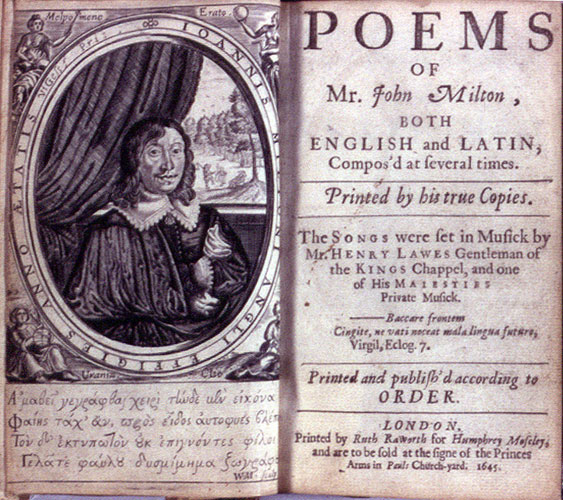

The illustration is Milton's contract with his publisher for the first, ten-book edition of Paradise Lost; he was paid only ₤5 for the rights! Thanks to the University of South Carolina Library for the image: http://www.sc.edu/library/spcoll/britlit/milton/4island1.JPG