T. S. Eliot

(1888-1965)

T. S. Eliot

(1888-1965) T. S. Eliot

(1888-1965)

T. S. Eliot

(1888-1965)Terms: near rhyme, free verse, allusion, Imagism, objective correlative

Imagism (source: http://www.mala.bc.ca/~mcneil/m4lec13a.htm)

The first important artistic tenet of Imagism was that the poet must get rid of the omnipresent voice of the poet, the Wordsworthian "I." Whatever poetry was about it must reject the wallowing in subjective emotionalism, and instead focus on the peeling away of the layers of skin surrounding the poet's psyche. The second tenet, from which the movement derives its name, is that whatever the poet has to communicate, he or she must do so in terms of objective images: clear, objective, precise, concentrated, and fresh symbols which capture, in the way they are presented the emotional qualities under exploration. "The image is itself the speech," proclaimed Pound. Poets should not be telling us how they feel—they should be presenting us with impersonal images which capture the feeling, so that we, as readers, can react to the image without the meddlesome interference of the poetical personality (the "I"). Poems, in other words, should not be interpreting the experience for us; they should provide the objective means by which we can ourselves, as readers, discover what matters. Thirdly, Imagist practice demanded a break with the old conventions of writing verse, especially with a standard rhythm and rhyme. They declared inappropriate the traditional war horse of English poetry, the iambic pentameter-the medium for virtually all the major poets since Chaucer (Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden, Pope, and so on). Modern verse should emancipate itself from the notion that the language had to fit some preconceived pattern-the pattern should emerge from what was demanded by the language at that particular moment.

Hence, Imagism promoted what came to be called "free verse," liberating the poet from traditional conventions of set rhythms and rhyme and insisting that the formal properties of the poem were to take shape flexibly in the ways best suited to the achievement of the appropriate form of language. Hence, centuries of formalist restrictions were done away with, and a new characteristic of modern poetry emerged--the constantly shifting rhythmic patterns, changing with the particular sections of the work. The Waste Land is one of the finest examples of this, moving from blank verse, to song, to prose, to music hall speech, in short, to whatever the requirements of the particular lines. Gone is the traditional regularity which for so long had defined poetry (and which, for many, still does). Imagists insisted that free verse does not mean that anything goes. No verse is free for the poet who really wants to do a good job Pound claimed. And he grew frustrated at the ways in which, under the banner of Imagism, all sorts of ineffectual experiments justified themselves (see Letter to Harriet Monroe, 1 August 1914 and January 1915). What Pound wanted was a new form of poetic discipline.

One can sum up many of these points in one injunction. Modern poetry must address the modern world with modern language and images appropriate to the modern experience, unfettered by the conventions which had grown up over the centuries.

The Imagists saw themselves as kinds of empirical scientists, like the Royal Society—they are reporting experience as it is seen and felt. In a sense, they were a kind of anthropologist. Eliot went so far as to argue that the only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an "objective correlative"; in other words, "a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion; such that when the external facts, which must terminate in sensory experience, are given, the emotion is immediately evoked" (lecture on Hamlet and His Problems).

What Eliot means here is that the job of the artist is to find a fictional equivalent to the emotion he wishes to explore, something adequate to the complexity of the feeling which is at issue--the images must be adequate to the emotions, the source of our understanding of them, so that our response arises inevitably out of them, and not from being told directly by the poet what is at stake. In Prufrock's "Do I dare to eat a peach?" for instance, we see a situation where modern man feels so impotent and helpless that he cannot even make the simplest decisions anymore--the experience of deciding to eat a piece of fruit becomes the objective correlative by which Eliot explores the emotions of modern, overwhelmed humanity.

Prufrock (1915)

Dramatic monologue with modernist twist—fractured persona, breaking up the unified voice

Irony as mode of expression

Prufrock’s isolation, his inability to connect, the impossibility of any kind of love (think of how this is different from Early Modern love sonnets, for instance)

Vernacular voice—Wordsworth’s language of common man is real here

Violent and disturbing images—got the notion of the metaphysical conceit from Donne

Eliot wrote of Donne, "The ordinary man’s experience is chaotic, irregular, fragmentary"

American living in London—another outsider

What kind of romantic name is "Prufrock"?

Key passages: 1-3, 26-36, 45-48, 73-74, 81-86, 111-122

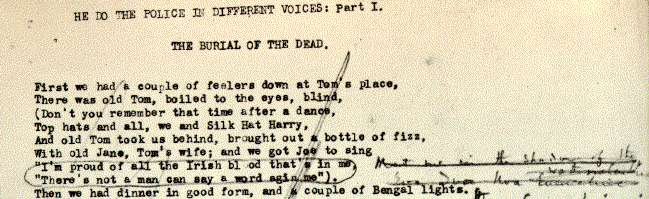

The Waste Land (1922)

Central poem of modernism

Universal themes of pessimism and alienation

Disjointed voices out of a wasteland, not able to connect

Spirituality is empty and dry

Shoring the fragments of civilization against its inevitable doom—mutability with a modern feel

Breakdown of social, cultural, communal, and personal relationships

The waste land in Jessie L. Weston’s From Ritual to Romance is the land of the Fisher King of the Holy Grail legends, the sterile land with the maimed king that can only be healed by the coming of a Grail and Grail Knight (who in Eliot is nowhere to be found) to heal the King and take over as the leader of the land.

Key passages (all of it!)--