Thomas Gray was one of the most important poets of the eighteenth century. This scholar and poet was the most famous for his poem "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard." Thomas Gray was born on December 26, 1716 in London. He was the only child in his family of eight to survive infancy. His father was Philip Gray, a scrivener and exchange broker who treated his wife with extreme cruelty. As a result, Dorothy Antrobus Gray left him several times. It was Gray's mother who saw to her son's education, running a millinery business to earn money for Gray's education. At the age of eight, he was sent to Eton College where her brothers, Robert and William Antrobus, were teaching. (Eton College is neither public nor a college but a prep school for wealthy boys who expected to go to Cambridge or Oxford.)

Eton gave him companionship with other boys, especially with ones who had the same interests, such as books and poetry, as he did. It was here where he and his three friends—Horace Walpole, later the architect of Strawberry Hill and inventor of the Gothic novel as well as the son of England's prime minister; Thomas Ashton; and Richard West, son of Ireland's lord chancellor and grandson of the famous Bishop Burnet--formed the ‘Quadruple Alliance’ which would play an important part in his adult life, and many scholars now believe that it was in this environment that he first realized he was gay.

In 1734 he entered Peterhouse College, Cambridge University, where he studied for four years. He decided not to take a degree; instead, he decided to go on and study law at the Inner Temple in London. He made a Grand Tour of the continent with Walpole (who paid all the expenses) in 1739. The two had a falling out, for reasons that are not known, and Gray concluded the tour alone and returned to London in September 1741. He was not reconciled with Walpole until 1745. After Gray's return from the Continental tour, his father died. His mother, aunt, and he moved to the village of Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire.

When

his best friend, Richard West, died of tuberculosis at the age of 24 in 1742,

Gray wrote his first important English poems: the "Ode on Spring,"

"Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College," "Hymn to

Adversity." (See “Sonnet on the Death of Mr. Richard West,” Longman p.

2682). Here too he began his greatest masterpiece, "Elegy Written in a

Country Churchyard." It was these poems that solidified his reputation

although the total published work in his lifetime was very small-- a little less

than 1,000 lines, but those are considered to be perfect technical

accomplishments.

In October of 1742, Gray returned to Peterhouse College, Cambridge, as a Fellow-commoner (a student not pursuing a degree). In December of 1743, he took the degree of Bachelor of Civil Law (LL.B.) at Cambridge but never practiced. He remained at Cambridge, and tolerated it only because it had libraries to study Greek. He wrote and rewrote but was never satisfied; as a result, he left most of his work unfinished. The Internet Public Library notes that Gray wrote poetry in unpredictable bursts of activity. He said, "Whenever the humour takes me, I will write, because I like it; and because I like myself better when I do. If I do not write much, it is because I cannot." Gray was always reluctant to publish his works; had Walpole not printed some of them privately, many of the greatest poems in English literature would never have seen publication. His travel writings, however, became very popular and were very influential on Austen and the Romantics.

He was often with his mother and aunt at Stoke Poges. He traveled a great deal to London and to other parts of England, Scotland and Wales after his mother's death on March 11, 1753. On her tomb, he wrote that she was "the tender careful mother of many children: one of whom had the misfortune to survive her." When the British Museum (now the British Library) was opened to the public in 1759, he spent two years working in the great library. In 1762 he applied for the Regius Professorship of Modern History at Cambridge but only got the position (in 1768) because the successful candidate was killed. Although he was made professor of history at Cambridge, he never delivered any public lectures.

His health was always frail. At 55, Gray suffered a violent attack of gout and died in his rooms at Peterhouse on July 30, 1771. He was buried beside his beloved mother at Stoke Poges churchyard, the scene of the "Elegy". (The village of Stoke Poges has erected quite a memorial to Gray in honor of the poem.)

The Thomas Gray Archive has annotated online editions of the 14 poems published during Gray's lifetime, as well as biographical information and links to secondary criticism.

Literary historians usually identify Gray with a literary movement called sensibility. Where earlier neoclassical poets like Swift and Pope emphasized the rational powers of human beings, poets of sensibility turned their attention to the individual's capacity for sympathetic and empathetic emotional response. (Consider, for instance, Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, where rational and emotional approaches to life are so well contrasted.) The ability of the individual to respond with intense feeling to a scene or a subject is the primary interest of poems of sensibility. They want to evoke an emotional response from the reader: whereas neoclassical poets try to teach their readers how to think, poets of sensibility try to teach their readers how to feel. Again there is that need for moral instruction through literature, but the means of reaching the reader are different.

As we have noted, in the eighteenth century, the audience for literary works had broadened considerably, so poets tended to choose subjects that would appeal to the largest possible audience. In order to do this, they tended to favor the "general truths" of "nature", "human nature", and the English countryside. Poets of sensibility, therefore, tried to write poetry that would offend no one by avoiding direct commentary on the divisive issues of class conflict, religious strife, and the political world. But we should always remember that this avoidance suggests just how unsettled life in England was at this time: the more poets insist that their work "transcends" politics and history, the more unsettled their world is likely to be.

The English countryside was one of the most popular subjects of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century poetry for precisely this reason: the nationalism that poets used it to evoke tends to transcend class, religious, and political divisions. The England that we know today was not, of course, Gray’s or Pope's England. It was, for example, only one generation removed from a century of bloody civil wars of succession and religion that saw the execution of one king and the deposition of another. The educated English audience, therefore, could be expected to enjoy poetry that offered an escape from these issues. In response to the ever-changing social world, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English poets increasingly defined their work as “art” that transcends historical change. As a result, as the eighteenth century unfolds, English poetry comes to sound increasingly personal: poets use "public private voices" that base their claims to authority on their capacity for authentic emotional response.

Many elements of Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard and Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College indicate their place in the tradition of sensibility. Gray writes these poems in first person, but unlike Pope, he does not speak to a specific listener. Instead, he writes dramatic monologues—in other words, extended soliloquies, in poetry rather than in drama. The poems ask us to imagine that we, as readers, overhear the speaker talking to himself and reflecting on the scene before him: they ask us to believe that we listen in on the speaker's private thoughts. As you read these poems, think about the relationship between form and content: how do they comment, fairly explicitly, on political or generic issues while claiming to represent the speaker's stream-of-consciousness?

Gray is regarded by many as a "pre-Romantic" because his poetry signals a shift from the characteristics of the Augustan age with its public focus, heroic couplets, and satire to the Romantic age with its focus on private thoughts, lyrical poems with alternating rhyme schemes, and exploration of the self. In the 18th century, art was regarded as artifice, thus the popularity of ornate, flowery language. The Romantics wanted art not to be so artificial. Gray's poems reveal the characteristics of both literary periods. For example, in "Eton College," Gray describes the young boys swimming in the Thames river with the line: "And cleave with pliant arm, Thy glassy wave," a style very much in keeping with the 18th century. Gray uses this poetic diction to establish his credibility because the language sets a certain decorum and appropriateness which his audience and critics would expect. Yet, these elite gestures are contradicted by a respect for the poor. He can fashion a poem that focuses uncharacteristically for his age on the poor and on the internal thoughts of the poet. It has been said that the Romantics discovered the poor; Gray comes pretty close. He further separates himself from Neoclassical poetry with his metrical innovation—he abandons the heroic couplet for metrically irregular and inventive stanza forms.

One of the most profound assumptions that Gray contributes to the study of literature is the notion that poets are not simply those who produce poems. For Gray, it involved having a certain sensitivity, whether the poet ever wrote or not. In other words, a poet was simply a certain kind of person. It has been said that for the 18th century, "heard melodies" are sweet; whereas for the Romantics, it is the "unheard melodies" that are best. Gray is best understood as a transitional figure between the two periods.

Ode on the Death of a Favorite Cat, Drowned in a Tub of Gold Fishes

This lovely jeu d’espirit was written about the death of Walpole’s cat Selima; Walpole asked Gray for an epitaph, but Gray responded differently. "I am about to immortalize [her] for one week or fortnight," wrote Gray to Walpole on 1 March 1747, adding at the end of the ode: "There's a poem for you, it is rather too long for an epitaph." The delighted Walpole had the first stanza engraved on the fatal Chinese vase, which is still on display in the Grand Salon at Strawberry Hill (a house that is well-worth visiting if you are ever near London).

The poem, a gentle mocking of the classical elegy we saw in Lycidas, tells the lamentable story of "demurest of the tabby kind/ The pensive Selima," who as both actual cat and symbol for avaricious and vain females, succumbs to temptation and drowns. The cat is reclining at the edge of an elegant china fish-bowl, like Milton's Eve, admiring her own reflection in the water. In elegant language far more elevated in tone than the situation requires, he describes the cat: "Her conscious tail her joy declared; / She saw, and purr'd applause." Her nemesis comes into view as she continues in this self-appreciation: two goldfish, "the genii of the stream," swim into her view, and she tries to capture them: "She stretch'd in vain to seize the prize,/ What female heart can gold despise?/ What cat's averse to fish?" "Malignant Fate" does nothing to help as the "presumptuous maid" tumbles headlong in. Gray combines the Neoclassical with the domestic in her feeble mews for rescue as she uses up her proverbial nine lives. "No Dolphin came, no Nereid stirr'd/ Nor cruel Tom, nor Susan heard./ A fav'rite has no friend!"

Gray's moral is tongue-in-cheek in reference to the cat's curiosity, but to the extent to which Selima represents the Neoclassical maiden eager for the world's riches, the moral is serious, implying watchful care about a fall of a quite different kind: "Know, one false step is ne'er retriev'd..../ Not all that tempts your wand'ring eyes/ And heedless hearts is lawful prize/ Nor all that glisters, gold."

Strawberry Hill

Stephen Elmer, “Mr. Horace

Walpole’s Favorite Cat” (1796)

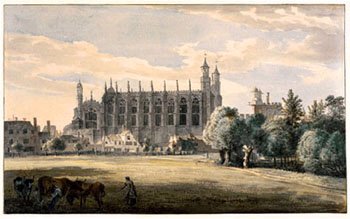

Paul Sandby, "Eton

College Chapel" (c. 1790s)

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

Gray worked on this poem from 1742 to 1750. Like Lycidas, it is a memorial to actual people, but a reflection on much more. In the poem, Gray makes the point that there is inherent nobility in all people, but that difficult circumstances prevent those talents from being manifested. He speculates about the potential leaders, poets, and musicians who may have died in obscurity and been buried there. At various stages of composition, the poem had several different endings. Critics do not agree about the merits of the differing versions. Some critics approve of the additional lines; others spoke of the new stanzas and the epitaph as "a tin kettle tied to the poem's tail. The poem now ends with the epitaph which sums up the poet's own life and beliefs.

Here rests his head upon the lap

of Earth

A Youth to Fortune and to Fame unknown.

Fair Science frown'd not on his humble birth,

And Melancholy marked him for her own.

Beginning with the eighth of the alternately rhymed decasyllabic quatrains, Gray contrasts the simplicity and virtue of the stalwart English yeomanry of the past with the vain, boastful present. The ambitious of the growing age of industrialism should not mock their "useful toil," nor cloud over their ‘'homely joys," nor hear a recitation of their "short and simple annals" with disdain. The lesson that their humble graveyard teaches is that whether life is blessedly simple, as it was for these rustics, or adorned with "The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow'r,/ And all that beauty, all that wealth e'er gave," the fact is that "the inevitable hour" awaits. To be sure, the grave is the terminus of the "paths of glory," but for the paths of the humble as well. The fact that no impressive memorials marked their resting places, nor "pealing anthems'‘ of funerals in "long-drawn alisle and fretted vault" does not matter. These displays of earth's glories make their honorees no less dead:

Can storied urn or animated bust,

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can Honor's voice provoke the silent dust,

Or Flatt'ry soothe the dull cold ear of Death?"

Gray then conjectures what losses may have occurred to art and science because these rural folk never could avail themselves of the opportunities that those of greater advantage could. Perhaps a would-be clergyman, with "heart once pregnant with celestial fire," or a potential great political leader with hands "the rod of empire might have sway'd," or poet who might have "wak'd to extasy the living lyre" lies in the cemetery. But their careers were stanched by the dual forces of ignorance and poverty. Knowledge did not reveal to them "her ample page" laden with the "rich with the spoils of time," while "chill penury" disabled their creative spirits. As a result, their geniuses went to the grave unblossomed, just as (in a reference to Lycidas)

Full many a gem of purest ray serene

The dark unfathom'd caves of ocean bear;

Full many a flower is born to lush unseen

And waste its sweetness on the desert air.

With a sense of futility, Gray notes that all life's endeavors, whether positive or negative, are rendered useless by the shadow of the tomb. To be sure, some "village Hampden" (that is, a benefactor of the people) or "mute inglorious Milton" may have been stifled by rural poverty and inaccessibility, but likewise a potential dictator (Gray was a Tory) such as Cromwell may have been saved from shedding "his country's blood." Here is the poetic consolation, not only for the dead but the living, conservative poet; destiny has shut off from them the very avenues of advancement associated with the oligarchy of 18th century England, so that none of their rank will ever be glutted with "th' applause of listening senates," nor will they ever read their histories in the chronicles of the nation. Gray's Tory position, then, used here almost to justify their poverty, is that destiny confined not only their "growing virtues" but "their crimes confin'd" as well. From their ranks no one will "wade through slaughter to a throne," or open eyes of mercy on humankind. In the most often quoted (or misquoted) line in the poem, Gray says that their aspirations never deviated very much from the quietude that lies "Far from the madding crowd's ignoble strife." Instead, they adhered to the "cool sequester'd vale of life."

Turning his attention to the unsophisticated memorial stones in the cemetery, Gray notes the "uncouth rhymes and shapeless sculptures" which call from the sentimental passerby the "passing tribute of a sigh." The scriptural texts which adorn them "teach the moralist to die," yet even these simple memorials call for us, the living, to see that we still share in their humanity: "Ev'n from the tomb the voice of Nature cries,/ Ev'n in our ashes live their wanted fires."

In the conclusion of the poem, Gray recognizes that as he contemplates the efforts, hapless as they may be, of these rustics to insure some kind of earthly immortality through their tombstones, he is giving voice to his own impulse toward immortality. Neoclassical decorum demands, however, that he remove himself from the poetic expression; therefore, he conjures up a persona, one who "mindful of the unhonor'd dead" did their "artful tale relate." And "hoary-headed swain" will tell the "kindred spirit" passer-by that this poet could in times past be seen meeting the sun at early dawning, wandering through the forests and by the brook all day: "Now drooping, woeful wan, like one forlom,/ Or craz'd with care, or cross'd in hopeless love." But mortality claimed him at last. The passer-by is asked to read the epitaph of this "youth to Fortune and to Fame unknown." The stressing of both human knowledge and piety suggests Gray's own image of himself. "Fair Science frown'd not on his humble birth,/ And Melancholy mark'd him for her own." Large in kindness as well as holiness, this self-projection of the poet lies (as eventually Gray would be buried beside his mother in the Stokes Poges churchyard) trusting not in human endeavor but in "the bosom of his Father and his God." In such terms, he agrees with both Pope in The Essay on Man and Johnson in The Vanity of Human Wishes.

Many critics point out how the poem conveys so perfectly what others have always felt. Its reflections on fame, obscurity, ambition, and destiny tend to sound as if they have always been written in stone. Samuel Johnson said, "I have never seen the notions in any other place; yet he that reads them here, persuades himself that he has always felt them." If you remember Pope’s definition of wit in The Essay on Criticism (“What oft was thought, but ne’er so well expressed,”), Gray’s Elegy is the perfect example of neoclassic wit in action. In many ways, the poem has become the representative poem of its age. It is still one of the most popular and best-loved poems in the English language.

Note:

some of the material above was drawn from the McDaniel lectures on British

Literature at http://www.nortexinfo.net/McDaniel/1-16neocl.htm.

Some factual material was drawn from the Internet Public Library site on

Gray.