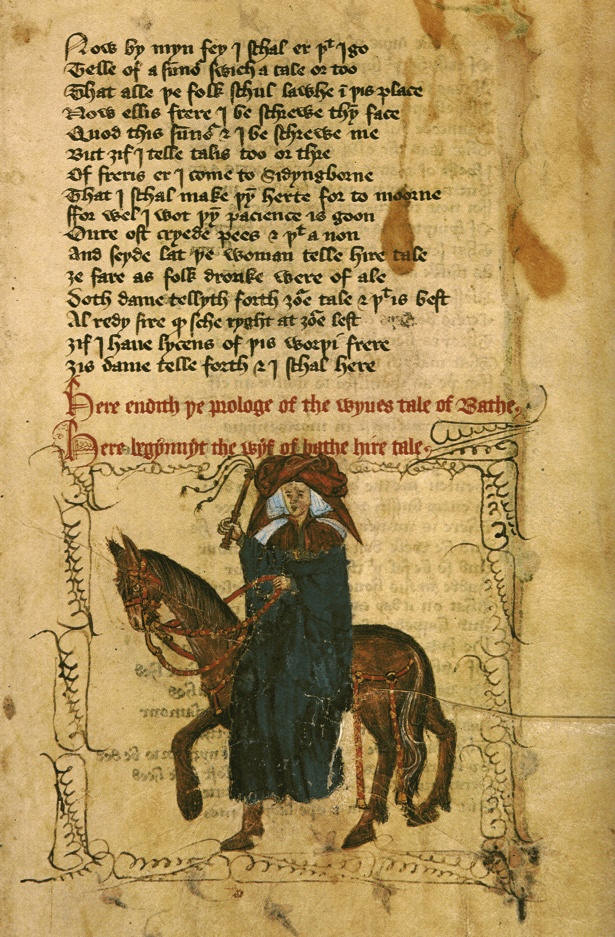

The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale, the Parson's

Prologue and Tale, and the Retractions

Key terms: antifeminist or misogynist literature; romance;

flat vs. round characters; experience, auctoritee, maistrye,

spiritual autobiography, mystic

The

Middle Ages had, to put it mildly, a woman problem.

Women were part of two of

the three estates (those who worked and those who prayed), but yet they were

also a fourth estate outside the system. They were viewed—legally, morally, and

spiritually—as extensions of the men in their lives, dependent upon either a

father or other kinsman as protector, or legally identical to their husbands. It

was very rare for a woman to be a femme sole under the law and own

property; medieval law was far more comfortable with femmes couvert,

women who were “covered” by some man’s control. (In fact, in the 15th

century, the average time for a London mercantile-class widow to remarry was

around a month.)

The

Middle Ages had, to put it mildly, a woman problem.

Women were part of two of

the three estates (those who worked and those who prayed), but yet they were

also a fourth estate outside the system. They were viewed—legally, morally, and

spiritually—as extensions of the men in their lives, dependent upon either a

father or other kinsman as protector, or legally identical to their husbands. It

was very rare for a woman to be a femme sole under the law and own

property; medieval law was far more comfortable with femmes couvert,

women who were “covered” by some man’s control. (In fact, in the 15th

century, the average time for a London mercantile-class widow to remarry was

around a month.)

The Church provided the underpinning for this status. It

saw women as essentially duplicitous. One the one side, they were images of the

Virgin Mary—the mother, nurturer, intercessor, chaste and worshipped on their

pedestals. The term used by Gabriel to greet Mary in the gospels—Ave gratia

plena [Hail, full of grace!] is used to summarize this position.

At the same time, the Church taught, women were descendents

of Eva [Eve]—and thus instruments of temptation and sin. They were

carnal, not spiritual; they dragged men down by the lure of their physicality.

When men desired a woman spiritually, they committed a sin; thus, women were the

instruments of men’s damnation.

Men were expected to chastise women—to keep them in their

place, reduce their ability to tempt me, and above all maintain control (maistrye

or sovereintee) over the women in their lives. (Wife-beating or

daughter-beating was in fact legal within certain constraints, since women

obviously were so intellectually weak that you couldn’t convince them to change

their ways through reasoned argument. <<irony!!!>>) Letting a woman run things

is an admission that men were not doing their spiritual duties. A whole genre of

misogynist or antifeminist literature sprang up that told of the dangers caused

by wicked women—much like the book Jankyn reads to Alys.

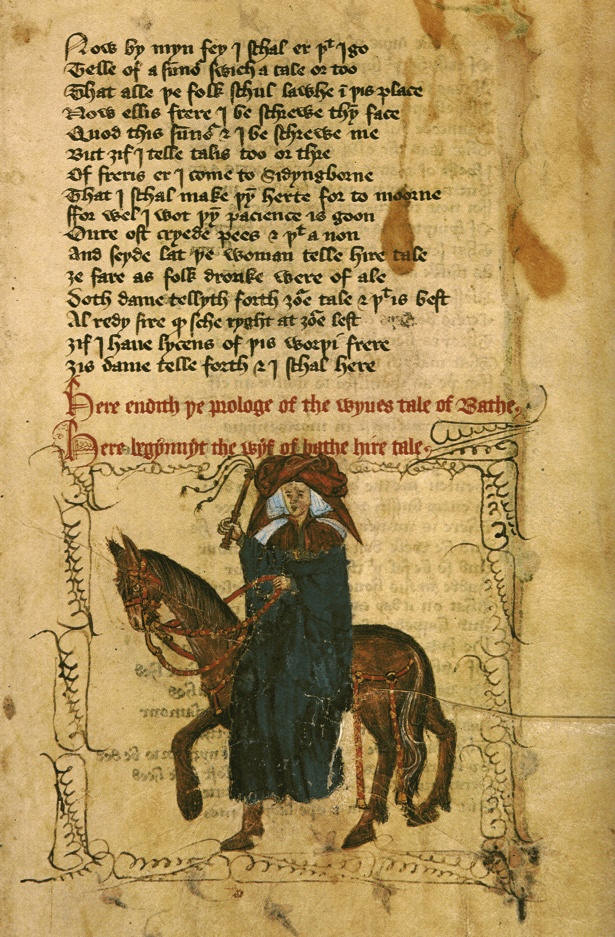

So when Chaucer comes to represent a carnal woman in the

Canterbury Tales, he has a difficult choice to make: does he represent the

Ave side or the Eva side? He chooses Eva, and in doing so,

creates the first round character in English literature—the Wife of Bath.

Evidence in the unfinished Tales suggests that

Chaucer originally had a more flat, stereotyped character in mind for the Wife,

who probably would have told the very coarse fabliau that survives as the

Shipman’s Tale. Instead, as he created her character, he seems to have fallen in

love with his own creation—and the Alys he creates jumps off the page at us as a

vibrant, if spiritually misguided figure.

From her first sentence—“Experience, though noon auctoritee

is in this world, is right enough for me to speak of wo that is in marriage”—Alys

announces to us that she is arguing on the devil’s side, for the evidence of

physical senses (the province of the lewed) against the learned auctoritees

of clerks, government, and the Church. She turns the biblical texts upside down

to make her case that God intended women to use their bodies carnally—that after

all, if women didn’t have sex, where would the next generation of virgins come

from? She has no problem with those who choose virginity or a more spiritually

“pure” life, but she argues vigorously for the fact that using her “instrument”

with her husbands does not condemn her. In a series of famous metaphors—gold vs.

wooden dishes, white vs. barley bread, the flour vs. the bran of a grain of

wheat—she argues that who she is and what she does are perfectly defensible from

a spiritual sense. Like the Pardoner, the Wife is a vice character whose

prologue is a confession of her techniques and an exposure of her sins—yet

unlike the Pardoner, we warm to her because of her [that is to say, Chaucer’s]

good humor, her liveliness, and her considerable rhetorical skill.

She has had five husbands (and is seeking a sixth): three

elderly rich ones, whom she nagged constantly but also satisfied sexually; a

fourth “revelour” with whom she had epic sexual battles; and her fifth (and

‘true love’) Jankyn, the young clerk who marries her for her money and makes her

life a living hell by beating her, reading her antifeminist literature,

literally deafening her, and finally almost killing her. Only when he fears he

has killed her does he relent and grant her maistrye—which she

embraces by socking him in the face, then turning around and telling a tale of

what would happen if women ran things.

Her Tale, a romance, has a lady rescuing a knight

rather than a knight rescuing a lady. In an uncanny prefiguring of Freud’s

famous “What do women want,” Chaucer has the Wife tell a story of a man’s search

for the answer to that question. When he proves to be surly and unappreciative

of the woman who gives him the answer, she lectures him on gentilesse—the

true nobility of the spirit—which comes not from high-class birth but from the

soul. (How deeply ironic—in a tale whose message overthrows everything a good

medieval Christian should have believed—to have this sermon, which is apparently

“straight,” and full of sound advice.) The knight, finally chastised, yields the

sovereintee or maistrye to his wife, and in doing so gets the

happy ending he wants. The Wife’s solution reinforces her Prologue and at

the same time sets medieval spiritual values on their ear by arguing that women

should run men’s lives, and not vice-versa. She is the ultimate rebel—and you

have to love her.

The measure of Chaucer’s unease with what he created is

seen both in the Parson’s Prologue and Tale and in his Retractions,

which circulate with most copies of the Canterbury Tales. The Parson’s

Tale is a translation and adaptation of a catechism—a manual teaching strict

and standard Christian beliefs. In the “Remedy for the Sin of Lechery,” the

Parson strictly defines a wife’s duty to her husband, a husband’s

responsibilities to his wife, the limitations on sexual conduct consistent with

Christian moral practice, and celebrates chastity—all in direct contrast to the

Wife’s ebullient argument. If the Parson is an ideal figure, we have to assume

that his version is what Chaucer and his society thought was the “right”

conduct—but the popularity of the Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale

suggests that her argument, too, had its enthusiasts.

When Chaucer in his Retractions (traditionally

believed to be the last thing he wrote) apologies for those works that might

lead people into sin (by being too morally subtle or by making sin too

appealing), he is apologizing (and at the same taking pride in) works like

The Wife of Bath’s Prologue and Tale. It is one of the marks of his

greatness that he can reflect so many sides of a complex moral picture without

forcing a decision upon us—that he, in fact, trusts us as readers to evaluate

the conduct he portrays and the stories he tells and make our own judgments

about them.

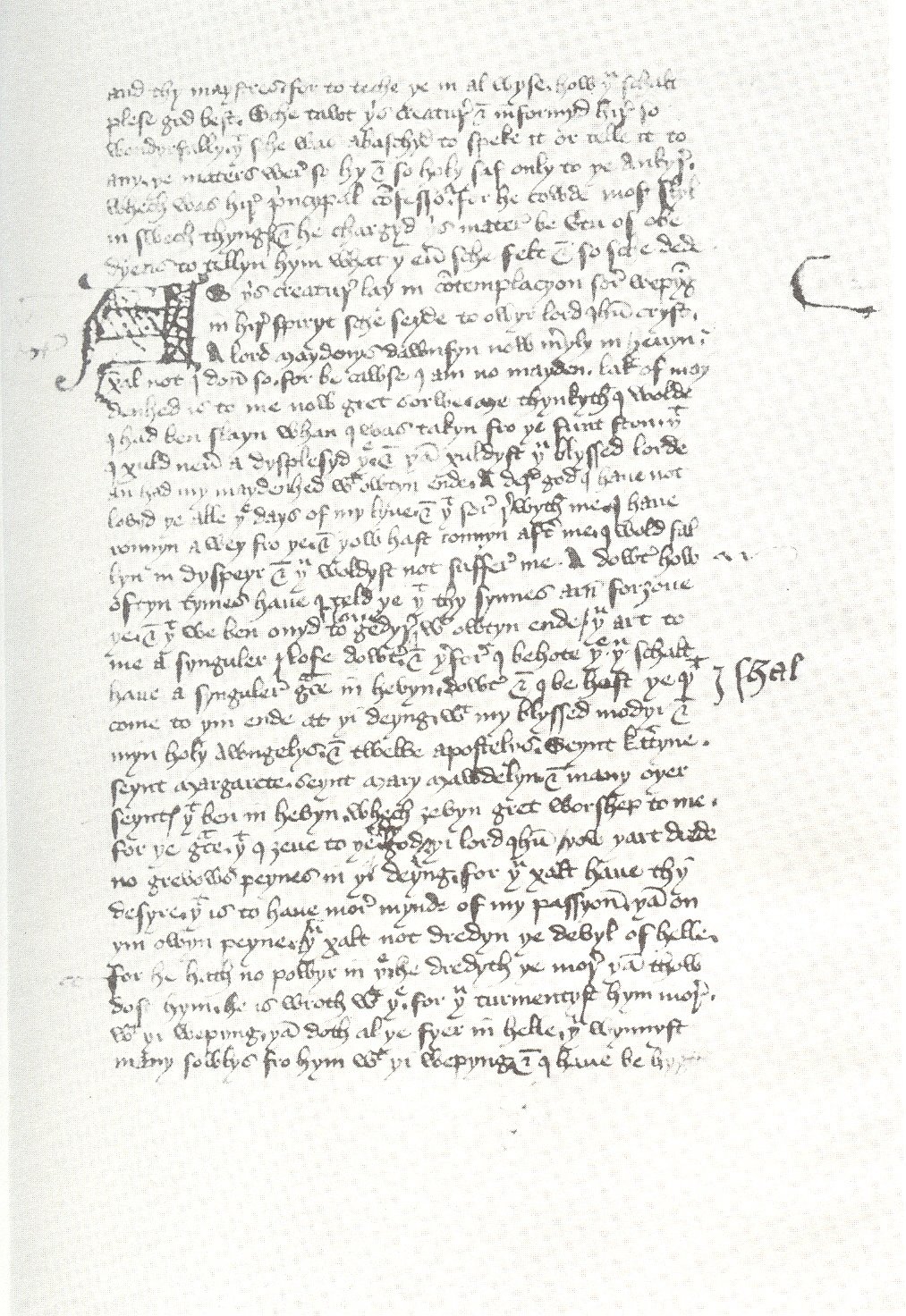

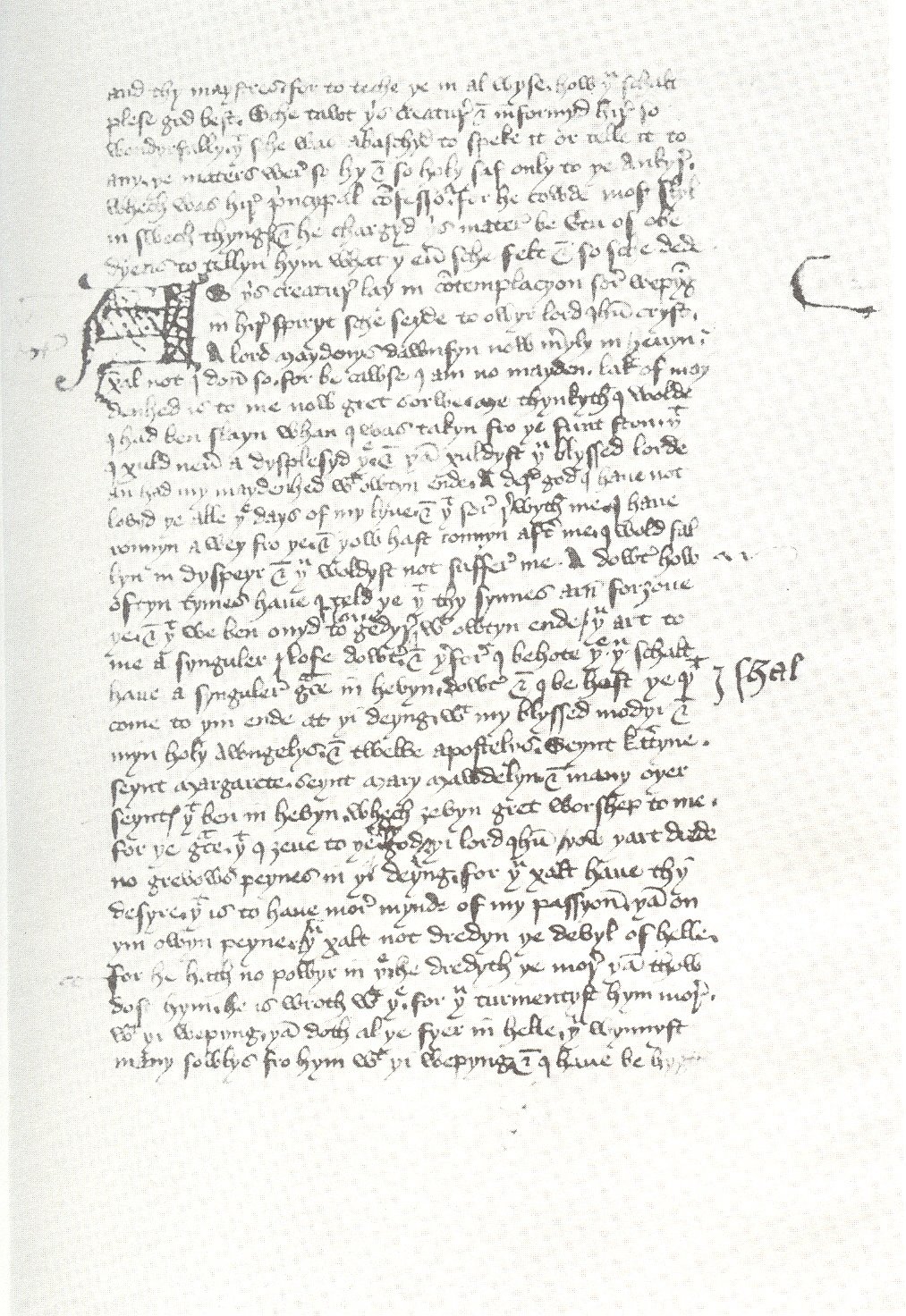

The Book of Margery Kempe

(Margery Kempe,

c. 1373—after 1438)

Biography

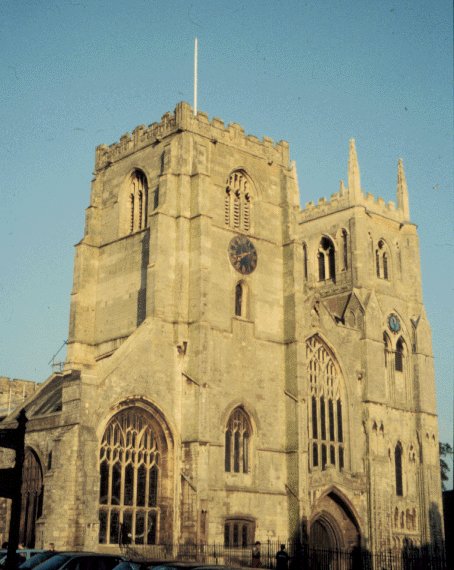

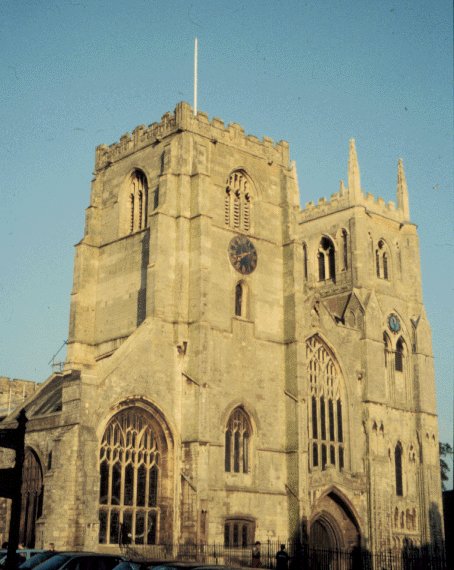

from St. Margaret’s Church

An eight-page pamphlet was published by Wynken de Worde in a 500-copy edition

entitled A Short treatise of contemplation taught by our Lord Jesu Christ,

taken out of the book of Margery Kempe of Lynn. All but one copy, in

University College, Cambridge, perished, and scholars placed Margery among the

English mystics of the period, of whom there were many, such as Hilton, Rolle,

and Juliana of Norwich. In 1934, Hope Emily Allen was allowed to look at a

manuscript in the library of Col. Butler Bowdon of Pleasington Old Hall in

Lancashire. A scholar of Robert Rolle, she soon discovered that it was the book

from which de Worde had derived his pamphlet, but that it was not a book of

devotion. Instead, it was a rather massive autobiography; the first written in

English, and one of the few deep personal insights we have into the life and

thoughts of a member of the middle class of the period.

Though the manuscript was probably copied several decades after her death, it

remains our vital link to this intriguing figure in the development of medieval

thought.

Margery Kempe was the daughter of John Burnham, five times mayor of the town

of Lynn, a flourishing town of Norfolk. In 1393, Margery married John Kempe, a

young merchant of the town, and a member of the same Corpus Christi guild as her

father. Her marriage was an uneasy one, affected by, among

other factors, Margery's post-partum depression after the birth of her first

child, her increasing spirituality, and her battles with her very worldly (and

probably understandably confused and antagonistic) husband, who appears to have

been constantly in debt and at odds with his wife until later in life, when he

became seriously ill and she nursed him.

The

King's Lynn of Margery's time was a flourishing mercantile center that

participated in a great deal of England's lucrative textile trade with the Low

Countries (Belgium, Holland, and northern Germany--all of which Margery lumps

together as "Deutschland"). The guilds of Lynn were powerful and profitable, and

a woman of Margery's connections would have been a socially recognizable person.

(See the picture of the medieval Guildhall in Lynn, on the left.) Though she

would probably have learned little to no Latin, and therefore been considered

"illiterate" by the standards of the lerned, she was undoubtedly given

enough schooling in the vernacular to read basic prayers, keep household and

business accounts, and pursue her interests in reading--which she describes

thoroughly in her Book. However, literacy among the lewed

The

King's Lynn of Margery's time was a flourishing mercantile center that

participated in a great deal of England's lucrative textile trade with the Low

Countries (Belgium, Holland, and northern Germany--all of which Margery lumps

together as "Deutschland"). The guilds of Lynn were powerful and profitable, and

a woman of Margery's connections would have been a socially recognizable person.

(See the picture of the medieval Guildhall in Lynn, on the left.) Though she

would probably have learned little to no Latin, and therefore been considered

"illiterate" by the standards of the lerned, she was undoubtedly given

enough schooling in the vernacular to read basic prayers, keep household and

business accounts, and pursue her interests in reading--which she describes

thoroughly in her Book. However, literacy among the lewed

was a dangerous, even potentially heretical skill in early fifteenth-century

England--and Margery lived in East Anglia, where anti-Lollard persecutions were

particularly fierce. Thus, she is always careful to stress that her reading is

conducted under the guidance of a spiritual director (usually a priest or monk);

that she does not "preach" but merely carries on "holy conversation;" and that

she cannot translate Latin without divine inspiration. Drawing on the models of

the lives of women like St. Bridget of Oignes, she either created the persona of

or actually used the services of a priest who wrote down her experiences for

her--thus covering her experience with the patina of auctoritee.

Many scholars repeat the statement that "Margery Kempe was illiterate" without

much consideration--but the evidence shows otherwise.

The Book is the spiritual autobiography of a medieval person

who believed she had genuine religious visions—and was compelled to witness to

her faith in ways that were far from normal in her time—especially for a woman.

In studying Margery, it’s always important to think about what role gender plays

in her actions and in her text—you might want to pay close attention to her

imagery and language choices as she describes her experience. Margery's visions

are accompanied by fits of tears and crying, and she seems to want us to feel

what Christ experienced—to put us in her and His shoes, as it were. In the

Middle Ages this was called "affective piety" and you may have experienced it

today if you have heard a sermon in an evangelical church, where it remains a

major factor in spirituality. So Margery too is emphasizing experience,

the kind of knowing available to the laity, over auctoritee, the

whole closed tradition of book learning that was controlled by the male clergy.

It’s worth considering how her emphasis, however, differs from Alys of Bath’s

focus.

As

Lynn Staley notes in her

Introduction to

the Book, "By presenting Margery as living out a

vernacular gospel, as appearing sometimes to preach that gospel, and as

challenging the authority of confessors, priests, and bishops, Kempe sketches in

the outlines of a nation where conformity has become an end in itself and where

anyone, particularly a woman, who seeks to imitate the Christ-like life has

trouble finding tolerance, much less approval. Just as she explores the

materialistic and conformist nature of the England of Henry V, Kempe provides a

sharp look at the ecclesiastical institutions of the day. By blurring the

distinction between the ecclesiastical and secular spheres, Kempe suggests ways

in which churchmen too often resemble their secular counterparts in their desire

for conformity, worldly status, wealth, and power."

As

Lynn Staley notes in her

Introduction to

the Book, "By presenting Margery as living out a

vernacular gospel, as appearing sometimes to preach that gospel, and as

challenging the authority of confessors, priests, and bishops, Kempe sketches in

the outlines of a nation where conformity has become an end in itself and where

anyone, particularly a woman, who seeks to imitate the Christ-like life has

trouble finding tolerance, much less approval. Just as she explores the

materialistic and conformist nature of the England of Henry V, Kempe provides a

sharp look at the ecclesiastical institutions of the day. By blurring the

distinction between the ecclesiastical and secular spheres, Kempe suggests ways

in which churchmen too often resemble their secular counterparts in their desire

for conformity, worldly status, wealth, and power."

Margery pursued a number of outlets to develop her

spirituality. She confered with mystics like Julian of Norwich; she traveled on

pilgrimage to Rome and the Holy Land (each time winning permission to travel

from her husband by promising to pay his debts); and she sought out

opportunities to engage in contentious debate with clerics who didn't live up to

her standards of what religious role models should be. It's interesting to note

that there are no records of her "trials" in the ecclesiastical court records of

Lincoln, York, or Canterbury, all of which survive from her lifetime. Likewise,

there are no records that she was persecuted or disliked in her hometown; the

last records of her show her being made member in a powerful religious guild and

bequests to her in return for prayers for the donors' souls. The question

therefore arises how much of her "autobiography" is true, and how much made up

to illustrate spiritual principles and models that she felt were important for

people to read about. Some people call The Book of Margery Kempe the

first novel in English. That's probably taking things too far, but we have to

remember that Margery shaped the tale she was telling for her own authorial

purposes, just like Chaucer shapes the Wife of Bath's story.

For all the eccentricities of her spiritual practice,

Margery's Book provides one of the first and best pictures of what life

was like for a real woman, contesting for her place and identity in the

male-controlled world of late medieval England. Her voice is as distinctive and

idiosyncratic as the Wife of Bath's, and taken together they offer us an

intriguing, if incomplete, picture of medieval English womanhood.

As a

wife and mother, Margery is no saintly virgin; she is far from an "estates

ideal" like the Parson or the Plowman in The General Prologue.

Compare/contrast her attitudes towards sex and the pleasures

of the flesh with the Wife of Bath. While the real and fictional women

are obviously very different (e.g. in their attitudes toward and enjoyment of

sex), do they have other things in common?

As a

wife and mother, Margery is no saintly virgin; she is far from an "estates

ideal" like the Parson or the Plowman in The General Prologue.

Compare/contrast her attitudes towards sex and the pleasures

of the flesh with the Wife of Bath. While the real and fictional women

are obviously very different (e.g. in their attitudes toward and enjoyment of

sex), do they have other things in common?

What is the reaction of different forms of authority (Margery's husband, the

church) to Margery's mystical experiences? How does the learned anchoress Julian

react to her? What role does gender play in these reactions? In the second

passage (NA 369), Margery accuses herself of pride-- which she regards as a sin.

Yet she is not exactly humble when she stands up to the Archbishop of York (NA

374-77). Why does she feel she can argue with the church authorities? The Wife

of Bath similarly argued for the validity of experience over scripture as a

source of authority in certain realms of human existence. Compare/contrast

Margery's and Alison's conflict with Church Authority. Who actually wrote

Margery's Book? In her case, are "author" and "authority" identical? Is

Chaucer's role analogous to that of Margery's scribe?

Study Questions for "The Wife of Bath's Prologue and

Tale"

1. What revealing details do we learn about the Wife of Bath's own

history in the first thirty lines?

2. What is the Wife opinion about virginity? How does she defend her

position?

3. The Wife bases her opinions about men upon her own extensive

experience. By way of defending her own actions, how does she explain the

relationship between herself and her first three husbands?

4. Since the Wife does not hold as scared all the moral precepts that are

part of the cultural basis of our society, how does she justify her

particular view about sexual relations between men and women?

5. The Wife sees relations between men and women as adversarial. Explain

how this informs her view of how those relations should be balanced.

6. What is the relationship between the Wife and her fourth husband? Is

their significance to her pilgrimage and his death?

7. Describe the incident that happens between the Wife and her fifth

husband, Janekin, the clerk (scholar). What are the various results of this

incident?

8. The Wife fashions her prologue so that her argument culminates just

before she tells her tale. What is the moral point she has been working up

to?

9. What are the effects of the interruptions in the Prologue? Who are

your sympathies, as a listener, with?

10. The tale, set in King Arthur's time, tells of a knight who must go

and find the answer to what question? Why is he sent on this journey?

11. What are some of the possible answers he is given along the way? What

is the correct answer?

12. Summarize what happens after he announces the answer.

13. What has the knight learned from the rape he committed, the quest set

by the Queen's Court, and his own acquiescence to the Fairy?

14. Is there any poignancy in the argument of the old woman when the

knight rejects her because she is foul and low when you consider the Wife

herself?

15. Revaluate the Wife's claim "Experience, though noon auctoritee/were

in this world, is right ynough for me/to speke of wo that is in mariage."

After comparing the man-woman relations at the end of the prologue and the

end of the Tale.

16. What similarities can you see between the tale of the Wife and "

Lanval" by Marie de France? What similarities between her life and the life

of Margery Kempe in the sections you have read?

17. How do you see the Wife at the tale's end? Is she a monster? An

apologist for women? An early feminist?

http://merlin.capcollege.bc.ca/fahlmanreid/wife_of_bath.htm

The

Middle Ages had, to put it mildly, a woman problem.

Women were part of two of

the three estates (those who worked and those who prayed), but yet they were

also a fourth estate outside the system. They were viewed—legally, morally, and

spiritually—as extensions of the men in their lives, dependent upon either a

father or other kinsman as protector, or legally identical to their husbands. It

was very rare for a woman to be a femme sole under the law and own

property; medieval law was far more comfortable with femmes couvert,

women who were “covered” by some man’s control. (In fact, in the 15th

century, the average time for a London mercantile-class widow to remarry was

around a month.)

The

Middle Ages had, to put it mildly, a woman problem.

Women were part of two of

the three estates (those who worked and those who prayed), but yet they were

also a fourth estate outside the system. They were viewed—legally, morally, and

spiritually—as extensions of the men in their lives, dependent upon either a

father or other kinsman as protector, or legally identical to their husbands. It

was very rare for a woman to be a femme sole under the law and own

property; medieval law was far more comfortable with femmes couvert,

women who were “covered” by some man’s control. (In fact, in the 15th

century, the average time for a London mercantile-class widow to remarry was

around a month.)

The

King's Lynn of Margery's time was a flourishing mercantile center that

participated in a great deal of England's lucrative textile trade with the Low

Countries (Belgium, Holland, and northern Germany--all of which Margery lumps

together as "Deutschland"). The guilds of Lynn were powerful and profitable, and

a woman of Margery's connections would have been a socially recognizable person.

(See the picture of the medieval Guildhall in Lynn, on the left.) Though she

would probably have learned little to no Latin, and therefore been considered

"illiterate" by the standards of the lerned, she was undoubtedly given

enough schooling in the vernacular to read basic prayers, keep household and

business accounts, and pursue her interests in reading--which she describes

thoroughly in her Book. However, literacy among the lewed

The

King's Lynn of Margery's time was a flourishing mercantile center that

participated in a great deal of England's lucrative textile trade with the Low

Countries (Belgium, Holland, and northern Germany--all of which Margery lumps

together as "Deutschland"). The guilds of Lynn were powerful and profitable, and

a woman of Margery's connections would have been a socially recognizable person.

(See the picture of the medieval Guildhall in Lynn, on the left.) Though she

would probably have learned little to no Latin, and therefore been considered

"illiterate" by the standards of the lerned, she was undoubtedly given

enough schooling in the vernacular to read basic prayers, keep household and

business accounts, and pursue her interests in reading--which she describes

thoroughly in her Book. However, literacy among the lewed