Key terms:

satire, Juvenalian satire, Horatian satire, Neoclassic Period,

Augustan Age, heroic couplet.

Key terms:

satire, Juvenalian satire, Horatian satire, Neoclassic Period,

Augustan Age, heroic couplet.Notes on Jonathan Swift (1667-1745)

Key terms:

satire, Juvenalian satire, Horatian satire, Neoclassic Period,

Augustan Age, heroic couplet.

Key terms:

satire, Juvenalian satire, Horatian satire, Neoclassic Period,

Augustan Age, heroic couplet.

Most of his reputation is based on Gulliver’s Travels: Brilliant

satire that is at once accessible to children and a sophisticated skewering of

18th century politics, mores, and morals. He is a Juvenalian

satirist, not a Horatian satirist like Pope: in Swift, you feel the pain of

being a man. He participated in the great 18th century philosophical

debate: are we basically benevolent and social (Rousseau) or selfish and brutish

(Hobbes)?

As a Christian moralist, Swift inherits the tradition of Milton—that pride

is the greatest sin, and that there is little altruism. He wrote to Pope,

"I have got materials Towards a Treatis proving the falsity of that

definition animal rationale [a rational animal]; and to show it would only be rationis

capax [an animal capable of reasoning]. Upon this great foundation of misanthropy….the Whole Building of my

Travels is erected." One of the great poems in which he shows this

is his anti-pastoral A Description of a City Shower (Longman

2449,

in which the conclusion of a rainstorm sweeping the trash-ridden streets of

London is "Sweepings from butchers' stalls, dung, guts, and blood, /

Drowned puppies, stinking sprats, all drenched in mud, / Dead cats and turnip

tops come tumbling down the flood" (2442), perhaps the greatest heroic

triplet of the age.

Note the importance of rationalism in Swift, especially at his most

satiric. He saw the irony in calling this "The Age of Reason" and went

after man’s capacity (or lack thereof) for critical thinking. He plays with

the manifestations of the Royal Society and the Plain Style of prose—A

Modest Proposal is a typical treatise with the most barbed sting of any

piece of prose in English. By taking on pieces like Petty’s Political

Arithmetic (pp. 2472), he stabs directly at the hypocrisy of a nation that

thought itself to be the most moral and Christian on earth while tolerating

these unbearably inhumane conditions.

Swift was an outsider all his life. He was an Anglican born to English parents, but born in Ireland, so while he had patronage in England through Lord Temple, he kept getting jobs in Ireland—which he really wanted to leave. He was originally a Whig (his early poems were published by Addison and Steele), but disgusted by Whig support for religious tolerance, he shifted to the High Anglican Tory party. He was installed in 1713 as Dean of St. Patrick’s, Dublin—the most important preaching post in Ireland, but of course, not the Dean of St. Paul’s London or a bishopric, which, to be honest, he would have gotten if he were English-born. He was capable of great warmth and friendship, as shown in his letters to friends and his Stella's Birthday poems, but he also was capable of close self-examination (Verses on the Death of Dr. Swift, probably the funniest poem in the 18th century canon and wonderful to read aloud--try the ladies playing cards for an example). You didn't want to get on Swift's bad side any more than you wanted to get on Pope's, as the poems make clear.

He took up the cause of Irish politics against the absentee, mostly Whig landlord real estate speculators. One of his major works was The Drapier’s Letters (1724-25), which successfully managed to turn public opinion against a government plan to impose debased coinage on Ireland. The British government offered a £300 pound reward to anyone who would reveal the anonymous author of The Drapier’s Letters. Despite Ireland’s crushing poverty and the apparent widespread knowledge in Dublin that Swift was the author, no one ever turned him in. The event made him a national hero, and he is one to this day. Though he became progressively more ill with a serious neurological problem that affected his balance and ability to speak, he still continued to defend the poor of Ireland until he became too ill to write or preach. In his will, he left more than half his estate to found the first mental hospital in Ireland as well to other charities.

Like most Tories, Swift had little sympathy for Whig politics, and when the Whigs attempted to further devalue the already third-world economy of Ireland through absentee landlordism, he wrote the brilliant satire A Modest Proposal to expose English hypocrisy as well as Irish lassitude (the unwillingness to fight back against injustice) he perceived. In the character of a projector who is trying to use the new science of economics to improve the life and moral condition of the Irish people, he perpetrates what Professor David Cody called "a ghastly masterpiece, cunningly devised, horribly plausible, deviously manipulative; it remains for the reader to come to terms with it, to comprehend it, and to determine the extent to which, oddly enough, it might be relevant in our own world." (Cody's analysis of A Modest Proposal is on the Victorian Web at Brown University.) I would also point you to Russell Hunt's article "Modes of Reading, and Modes of Reading Swift" at the St. Thomas University (Canada) website for an excellent analysis of reading Swift's works. A Modest Proposal has entered the language in many ways--there are literally thousands of works, all satiric, now called "A Modest Proposal" in imitation of Swift. (Don't believe me? Try the phrase in Google or AltaVista!) It is one of the great works of genius in English literature but alas, it made no real social changes happen--it simply, in a wonderful extension of empiricism to inhumanity, made it impossible for humanity to ignore the injustice it commits every day.

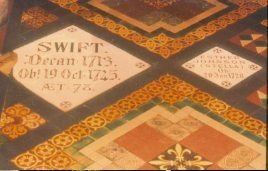

Swift is the first English writer to be known as a champion of

social justice. The epitaph on his grave in St. Patrick’s Dublin reads [my

translation of the Latin] "He has gone where fierce

indignation can lacerate his heart

no more. Go traveler, and

imitate if you are able one who fought with all his heart for the preservation

of liberty."

Swift is the first English writer to be known as a champion of

social justice. The epitaph on his grave in St. Patrick’s Dublin reads [my

translation of the Latin] "He has gone where fierce

indignation can lacerate his heart

no more. Go traveler, and

imitate if you are able one who fought with all his heart for the preservation

of liberty."