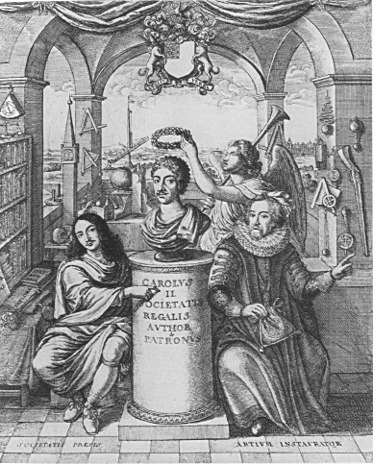

The picture on your right shows the frontispiece to Sprat's History of the Royal Society (1667). Its president, Elias Ashmole, points to a bust of the newly restored king, Charles, who is labelled "Author and Patron of the Royal Society" on the plinth of his statue, while the philosopher-scientist Francis Bacon, holding the seal of England, is labelled "Renovator of Arts." Bacon gestures at weapons and mathematical instruments while on the side of the president is a shelf of books. In the background are more scientific and navigation instruments, including an air pump and several sextants. The sweep of hand motions leads the observer to circle between books and instruments. No picture could better illustrate how pervasive the kinds of thinking the Royal Society fostered were in all aspects of Restoration England. You see this too in color plates 24, 25, and 26, which demonstrate how powerful and pervasive the notions of questioning and knowledge were in the times. And for trivia fans: the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society is the longest continually-published scholarly journal in existence, having appeared regularly since 1665 (though thankfully, the articles are no longer required to be in Latin).

In many ways the Enlightenment is both encapsulated by and characterized by the new, rational scientific approach to inquiry fostered by the Royal Society and its leading members, including Sprat, Hooke, and some guy obsessed with falling apples: ah, yes, Newton. It’s important to realize how comprehensive a movement this is: by focusing people’s attention on the kinds of inquiry that were conducted, the rigorousness and exactness required by research, the need to report results objectively and thoroughly, and the emphasis on logical, rational, describable processes, the Royal Society changed how we look at the world forever. Basically, they made us aware of the importance both of method and evidence, and the need for strict logical conclusions. Important passages in this section include Sprat’s description of the value of plain writing and the rational qualities of Englishmen (2126) and Hooke’s delineation of the scientific method for conducting any kind of research (2132-33). As you can see from Hooke's lucid prose, Restoration English readers might not know how many angels could fit on the head of a pin, but they could describe to you (thanks to the newfangled microscope) exactly what the point of that needle looked like. Cavendish's stylish and intelligent critique of the Royal Society (2151), while not exactly friendly to its aims, is an example of how these newly-popularized methods of critical thinking could be brought to bear on any activity in society.

We see the Royal Society’s

influence, too, in the daily writings of rather ordinary men, like Samuel

Pepys; his Diary (2086-2100)

is not only funny and gossipy but also shows the Society’s influence

in how a person reacted to the significant events of his life and times--that

"God is in the details," as a later wit would remark. Note how like

a scientist in a laboratory he notes the details of his life, how like Hooke he scrupulously examines

cause and effect, and how like Sprat he values plain speaking, in Cromwell’s

words, "warts and all." And, as is so common in the period, his chief

subject of study was himself—see the wonderful second

paragraph

on p. 2076 in Longman about the importance of self-reckoning. The notion

of the empirical Eye—the gaze trained to objective, rational scrutiny

and telling the truth, no matter how unflattering—is a legacy of this period.

All lenses--whether human or mechanical--were trained on the subject of the self

as a model of the greater Universe.

We see the Royal Society’s

influence, too, in the daily writings of rather ordinary men, like Samuel

Pepys; his Diary (2086-2100)

is not only funny and gossipy but also shows the Society’s influence

in how a person reacted to the significant events of his life and times--that

"God is in the details," as a later wit would remark. Note how like

a scientist in a laboratory he notes the details of his life, how like Hooke he scrupulously examines

cause and effect, and how like Sprat he values plain speaking, in Cromwell’s

words, "warts and all." And, as is so common in the period, his chief

subject of study was himself—see the wonderful second

paragraph

on p. 2076 in Longman about the importance of self-reckoning. The notion

of the empirical Eye—the gaze trained to objective, rational scrutiny

and telling the truth, no matter how unflattering—is a legacy of this period.

All lenses--whether human or mechanical--were trained on the subject of the self

as a model of the greater Universe.

Particular concerns of these thinkers were logic and order, and particularly concordia discors--the imposition of order on something that is inherently disorderly. One carryover of the Royal Society perspective is that the 18th century was a time when men believed that they could make everything in creation, and even God Himself, obey the rules of logic and order. Unlike the modern worldview, where we have come to believe that religion and science are diametrically opposed, they thought they could use mathematics, science, and empirical observation to understand and explain God’s creation and then recreate His actions in new works of beauty. (This to them was an act of faith in God, not a substitution for God.) Thus, the close examinations and descriptions of the natural world popularized by the Society were acts, truly, of devotion--they were opening up God's creation to man. They were great believers in imposed form--in artifice--that is, the creation (facere) of something beautiful (ars, artis). Today, at the turn of the millennium, we tend to look down on what is artificial; in the 18th century, artificial was the height of achievement, since it meant that some human being had imposed shape, order, design, logic, etc., on something that had previously lacked it. This was improving the world, imitating the actions of the Clockmaker God, and therefore was a Good Thing. That’s why wit is so important in the period: it was to impose human genius on nature, or as Pope says in The Essay on Criticism, "True wit is Nature to advantage dressed, / What oft was thought, but ne’er so well expressed." There was an emphasis in literature and other arts on imitation, symmetry, balance, and form--it’s the age of the Baroque, but also of classical imitations (remember Doric, Ionic, Corinthian?) and of easy grace and beauty. Craftsmen like Chippendale, Adam, and Capability Brown are most admired; Bach, Handel, Haydn, and eventually Mozart will rule music. Decorum, discipline, and order are the hallmarks. This is an age of controlled sprezzatura.