Key terms: scop, wyrd, fate, fyrd, elegy, ubi sunt, renown, complaint, The Exeter Book

The earliest surviving examples of Anglo-Saxon literature go back to 680 A.D., when a cattle herder named Cædmon wrote a divinely-inspired poem about the Creation at the monastery of Whitby where he worked. We know this because it was written down in 733 A.D. by the monk Bede, who quotes the poem in Latin (see p. 136); and a very very early copy of Bede's book, made in 737 C.E. (and now preserved in a library in Leningrad), has an Anglo-Saxon version of the poem written out in the bottom margin. This in a way is a very good example of how Anglo-Saxon literature survives--in chance copies, in margins, usually in books written down by clerics or their employees. This always raises the possibility of a tension: historically and culturally, the Anglo-Saxons were a pre-Christian [sometimes called 'pagan'] society. When their lives and culture were preserved by predominantly Christian scribes, there is the possibility that those scribes add a layer of "Christianization" to those stories, sometimes comfortably, sometimes uncomfortably.

Anglo-Saxon cultural order is social--whether in mead-hall or monastery. It is led by a powerful leader, the ring-giver, the hlaf-ford [lord or 'loaf-giver'] and hlaf-dige [lady or 'loaf-sharer'], who give rewards to faithful servants [the fyrd] who in turn have their own retainers. Retainers had the right to expect Lord to take their counsel--Æthelred the Unready's name means "Æthelred the Badly-Advised." Best way to die is in the noble service of one's lord; worst is to survive him and not be taken in by his heir or successor. Monasteries often dual (male/female); women as likely to be in charge as men. Tradition of extremely learned Anglo-Saxon nuns and abbots. Even there, the religious and lay servants would sit together at night, pass harp from one to the next and sing both heroic and lay tunes [attested in Bede]. The bonds between people in this society (especially between men) are very, very important to understanding how it worked.

Song/poetry very important in this culture: we're told that the Archbishop Ælfric used to stand on a bridge, singing secular songs at the top of his lungs, to attract a crowd for his sermons. One of the most valued members of this society is the scop (poet), who preserves cultural values and social history through his/her work. Originally this was an oral culture, but gradually, especially from about 733 onward for history and from about 900 onward for poetry, we get written copies of the scops' works. Scops were very important in memorializing your fame, which in the heroic cultures was how you were remembered. (You did something good, you gave the rewards to your lord, and he gave you gold back to honor you and had his scop compose a song in your honor. This is how reputations were established and bonds reaffirmed.)

Mixing of pagan and early Christian is important. Christianity comes to British Isles in 497 AD under St. Augustine of Canterbury and is only slowly accepted (See the "perspectives" reading on Bede). Eventually becomes organizing force for education (replacing Celtic Christianity, already established by missionaries from Ireland). Best Christian writers used the heroic motifs, just as the artists use native and Celtic animal forms in beautiful pages for the Gospel manuscripts they created. But the philosophic concepts didn't mix as easily. The Germanic heroic cultures emphasize what happens in this life--the bonds you form, the personal honor you demonstrate, the renown you earn, the gold you are given. In the Christian culture, peace is valued over war, the pursuit of worldly goods is rejected, this life is unimportant and only the afterlife in Heaven is what counts. For Christians, the glory that counts is the greater glory of God, not the greater glory of the self. We see in The Wanderer and even more clearly in Beowulf the heroic pre-Christian belief that fate ("wyrd") is all you have here, no immortality except the name you leave behind you, happiness is an earthly thing, your rank is determined by how much gold you win, in an uneasy tension with the Christian belief that earthly life is transitory, what happens here isn't as important as what happens to your soul, earthly rank is unimportant, give gold to Church/divest yourself of earthly possessions. The Wanderer is a good demonstration of that contrast--the lost man feeling his life is over because he's lost his lord, but trying to accept Christian stoicism at the end.

By form, elegy is a lament for something or someone lost, usually to death. No one knows how many speakers how many changes of speaker are intended in this poem; all punctuation is editorial (imposed interpretation by translator). Poem a contrast between heroic attitude (a man is lost when his lord dies and he has no troop, no friends to protect him) and Christian stoicism (endure all patiently; God will provide). Note the kennings (poetic metaphors) throughout.

Motif of ubi sunt ("where are they?") argues that the writer of the poem had exposure to classical literature and perhaps education. Other Old English poems also use this--probably very popular in a culture that had seen so much loss and radical political change. Clever Christians used it to show why people should believe in the eternal, not the temporal. (For Two Towers fans: the screenwriters use part of this passage in Theoden's arming scene.)

Questions to reflect on:

A. Individual and society: what relationships are valued between the lord/lady and their thanes? What behaviors, beliefs, and values does the society as a whole respect? Why are boasts so important? Why is fame (renown) so important? Why is fate (wyrd) so important? Why is story-telling so important?

B. Individual and faith: what role did faith play in an individual's view of himself? Did these figures see pre-Christian and Christian values as necessarily in conflict?

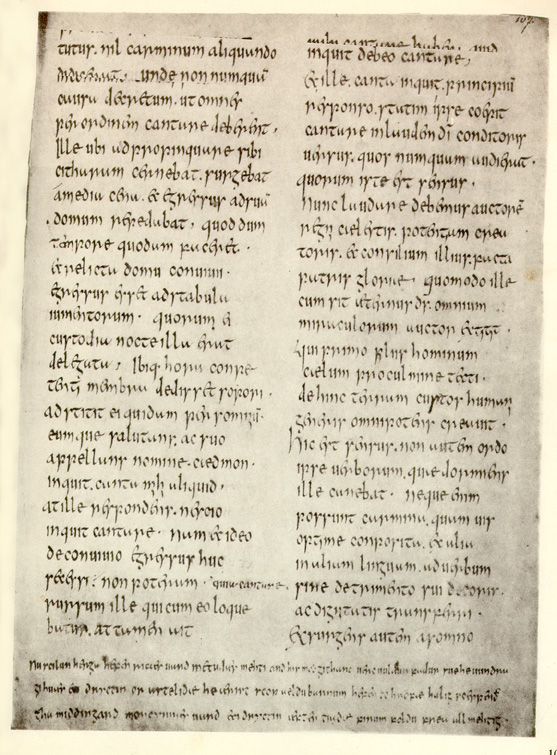

The Exeter Book of Anglo-Saxon Poetry (10th century; Exeter D. & C. MS. 3501): The Wanderer, 11. 1-33, f. 76v.

Picture courtesy of the Dean & Chapter of Exeter Cathedral

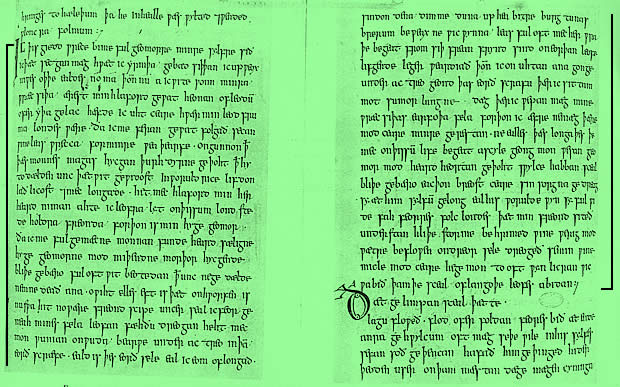

The great book we know as the "Exeter Book" was given to the library of Exeter Cathedral by the first bishop of Exeter, Leofric, who died in 1072. His will describes one great "englisc boc" which scholars believe could only have been the Exeter Book because of its extraordinary size. Its parchment leaves measure about 12.5 inches by 8.6 inches, slightly larger than a standard sheet of American paper, and the book originally probably contained a total of 131 leaves. It probably was written by a single scribe. At some time after Leofric's donation, but before its first study by a Renaissance antiquary named John Joscelyn, someone bound an additional eight leaves to its front, but also, the original first eight leaves were torn out, leaving the first original text (the hymn "Christ") lacking its beginning. The Exeter Book is our only surviving source for most works it contains, the most famous of which are "The Wanderer," "The Seafarer," "Widsith," "Wulf and Eadwacer," "The Wife's Lament," and a great collection of the witty riddles at which the Old English poets excelled. Source: http://faculty.goucher.edu/eng211/exeter_book_and_wanderer.htm

Reflect on