Historical facts: Chaucer born about 1343; died supposedly around 1400.

There's a short biography and an extensive chronology available on the

Harvard Chaucer Pages.

Historical facts: Chaucer born about 1343; died supposedly around 1400.

There's a short biography and an extensive chronology available on the

Harvard Chaucer Pages.Key terms: estates satire, iambic pentameter, couplets, enjambment, narrator, persona, frame narrative, worthy vs. trewe, vernacular

Historical facts: Chaucer born about 1343; died supposedly around 1400.

There's a short biography and an extensive chronology available on the

Harvard Chaucer Pages.

Historical facts: Chaucer born about 1343; died supposedly around 1400.

There's a short biography and an extensive chronology available on the

Harvard Chaucer Pages.

From middle-class family that owned a fair bit of land in London with ties to the Civil Service.

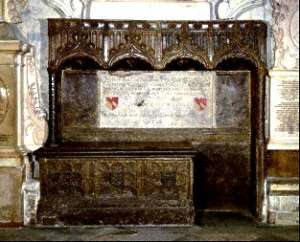

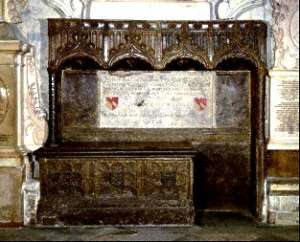

Chaucer’s first appearance in the records is as an esquire to a younger member of the Royal family in an account book in 1357. In 1359 Chaucer is a prisoner of war and in March 1360 the king helps pay to ransom him. We know that he is in royal service by 1366 and conducting trips to Europe on the king’s behalf. He also apparently married in that year a lady of the Queen’s household, Philippa Pa(e)n Roet, and his father apparently died in that year. Goes to Italy in 1372 for the first time on Royal business (probably because he already spoke Italian--he is the only native Englishman on the mission) and later undertakes secret negotiations for the Crown. In 1374 moves to the Aldgate. From 1374 to 1386 he is comptroller of the Customs. By 1386 has gotten himself out of the city and is one of the Justices of the Peace for Kent; in 1386 is also a member of parliament from Kent. Wife probably dies in 1387. In 1389 becomes Clerk of the King’s Works till 1391. In 1391 he was appointed deputy forester for North Petherton in Somerset. In 1399 he leases a house on the grounds of Westminster Abbey and apparently dies in 1400. He was the first writer buried in what's now called "Poet's Corner" in the Abbey (see picture above) it's important to remember that he was both writer and career civil servant--he didn't make his living as a writer. He had two sons, and his granddaughter Alice became (on her third marriage) Countess of Suffolk.

Chaucer as poet: At his time, "serious" religious, political, and

philosophical poetry was mostly in Latin, and "serious" art poetry was mostly in

French. Chaucer knew the works of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccacio and took from

them the inspiration to write serious poetry in his own native tongue, English.

Hit upon the happy idea to write

iambic-pentameter couplets, often

enjambed—native

music of English ear. Regarded as the "father of English poetry." He may not

have been the first writer to use this medium, but he was the first to make it

really popular and successful. In his lifetime, poets in both England and France

referred to him as the best poet living—even though he didn’t write poetry for a

living and was never publicly rewarded for doing so, he seems to have been

well-known, at least in London literary circles. Hoccleve's

portrait of Chaucer in his The Government of Princes (see picture on

right) is the first known surviving portrait of an English author.

Chaucer as poet: At his time, "serious" religious, political, and

philosophical poetry was mostly in Latin, and "serious" art poetry was mostly in

French. Chaucer knew the works of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccacio and took from

them the inspiration to write serious poetry in his own native tongue, English.

Hit upon the happy idea to write

iambic-pentameter couplets, often

enjambed—native

music of English ear. Regarded as the "father of English poetry." He may not

have been the first writer to use this medium, but he was the first to make it

really popular and successful. In his lifetime, poets in both England and France

referred to him as the best poet living—even though he didn’t write poetry for a

living and was never publicly rewarded for doing so, he seems to have been

well-known, at least in London literary circles. Hoccleve's

portrait of Chaucer in his The Government of Princes (see picture on

right) is the first known surviving portrait of an English author.

Chaucer’s Middle English is much like ours, though the pronunciation has shifted; silent –e is usually pronounced at the end of words (unless the next word begins with a vowel). Silent consonants (knight) were usually pronounced. Reading aloud is one of the best ways to get the sound of the poetry. The Chaucer MetaPage has lots of audio clips of Chaucer read aloud.

Chaucer’s poetic stance: Chaucer is always and deeply concerned with the state of human moral integrity (what he calls "troth" or "truth"). While the world around him judges people by surface values—what makes people ‘worthy’ is their economic status, their worldly reputation—Chaucer is much more interested in what makes people ‘trewe’—that is to say, morally admirable.

His genius is not to preach about this but instead to explore it through various degrees of humor, irony, and satire. The Canterbury Tales project is his masterwork—an attempt to look at many of the estates of society. Though unfinished, it gives us an idea of what he was wrestling with. He creates a frame narrative--a fictional pilgrimage from London to Canterbury and back--and creates a dramatic situation where the pilgrims tell tales on this journey that join, however imperfectly, together. (Chaucer apparently died before The Canterbury Tales were in their final form.) His lasting legacy comes partially because he chose to do this in the vernacular, in Middle English rather than the Latin or French that were considered the proper languages for serious poetry and serious moral works in his time. It's been said that Chaucer gave English poetry its music, and that is in many ways true.

The General Prologue is the key: we see an unnamed narrator meet up with and join "wel nine and twenty" pilgrims supposedly going to Canterbury as a pilgrimage to work off some of their sins. The narrator is a work of genius—he is at once gregarious and gullible and the details he reports to us are both humorous and really telling. Chaucer uses the persona of "Geoffrey the pilgrim" and his voice to manipulate us as readers. The "I" of the General Prologue is not Chaucer’s voice, but the voice of that gregarious and gullible puppet Chaucer creates to open our eyes to the human condition.

In the General Prologue Chaucer goes through all the human ‘estates’—those who fight, those who pray, those who work—and the fourth estate, those who are women. A few of his characters—the Parson, the Plowman, and probably the Knight—are ‘estates ideals’—those figures who live up to their moral responsibilities in the world and do what is right, always. (Look at the Parson & Plowman portraits, pp. 312-314, carefully.)

By contrast there are those figures who appear ‘worthy’ in the world and the

narrator’s eyes, but who are clearly not ‘trewe’: the Monk who rejects fasting

and poverty for fancy robes, fine food, and the hunting field; the Friar who knows

every girl and bar maid in town, carries gifts to bribe pretty girls and ends up

paying to marry them off; the Merchant, who dabbles in insider trading and

cooking his books; the Franklin, who is always stuffing his face yet is short on

true charity; the Wife of Bath, who cares more about what her neighbors think

and where she sits than what is actually going on in the Sunday church services.

Making his audience think about these people and their shortcomings is

characteristic of medieval "estates satire,"

the genre of literature that exposes such shortcomings for the readers'

reflection.

By contrast there are those figures who appear ‘worthy’ in the world and the

narrator’s eyes, but who are clearly not ‘trewe’: the Monk who rejects fasting

and poverty for fancy robes, fine food, and the hunting field; the Friar who knows

every girl and bar maid in town, carries gifts to bribe pretty girls and ends up

paying to marry them off; the Merchant, who dabbles in insider trading and

cooking his books; the Franklin, who is always stuffing his face yet is short on

true charity; the Wife of Bath, who cares more about what her neighbors think

and where she sits than what is actually going on in the Sunday church services.

Making his audience think about these people and their shortcomings is

characteristic of medieval "estates satire,"

the genre of literature that exposes such shortcomings for the readers'

reflection.

Chaucer isn’t a savage satirist (usually); more often, in his poetry, we get a sense of self-awareness, that he too knows how hard it is to think more about your soul than your worldly reputation, that he is aware how hard it is to avoid the occasions of sin, that he is painfully cognizant of the fact that humans are doomed to stumble and fall over and over again and desperately need the promise of divine forgiveness. Chaucer is the first in a long line of very very real, very very human, very very talented English writers to cast an insightful light on the human condition in its many stages. Chaucer can make us laugh or make us weep—but above all, what he wants to do is to make us think.

This is a picture of Canterbury Cathedral that I took from where the pilgrim's infirmary (resting place) would have been. It looks much the same as it did in Chaucer's day.