Sir Thomas Malory (c. 1410–1471)

Key Terms: "mirror for magistrates," chronicle, honor, Caxton, Winchester manuscript, mesure, troth

The best source I know about Malory's biography is Pete Field's Book The Life and Times of Sir Thomas Malory, and these biographical notes are drawn largely from Field's reseach, which builds on several earlier studies, including those of the late William Matthews. A short form of Field's book is the essay in Archibald & Edwards' A Companion to Malory, which you can also find in Dacus Library. Additional material is drawn from the Longman Anthology online material, at http://wps.ablongman.com/long_damrosch_britlit_2/0,6737,199713-,00.html.

In several of his colophons-those closing formulas to texts-the author of the Morte Darthur says he is "a knyght presoner, sir Thomas Malleorré," and prays that "God sende hym good delyveraunce sone and hastely." Scholars have traced a number of such names in the era, among whom two seem particularly likely: Sir Thomas Malory of Newbold Revell, and Thomas Malory of Papworth. The former Thomas Malory had a criminal record and was long kept prisoner awaiting trial, while the latter had links to a rich collection of Arthurian books. The Malory of Newbold Revell, who served as a member of Parliament and who appears to have been a partisan political player on behalf of the Earl of Warwick against the Duke of Buckingham, is now usually believed to be our writer.

The

Winchester manuscript notes that "the hoole book of kyng

Arthur and of his noble knyghtes of the Rounde Table" was completed in the ninth

year of King Edward IV, that is 1469--1470. So "whichever Malory wrote the

Morte d'Arthur, he was certainly working in the unsettled years of the War

of the Roses, in which the great ducal families of York and Lancaster battled

for control of the English throne. As one family gained dominance,

supporters of

the other were often jailed on flimsy charges" (Longman).

The

Winchester manuscript notes that "the hoole book of kyng

Arthur and of his noble knyghtes of the Rounde Table" was completed in the ninth

year of King Edward IV, that is 1469--1470. So "whichever Malory wrote the

Morte d'Arthur, he was certainly working in the unsettled years of the War

of the Roses, in which the great ducal families of York and Lancaster battled

for control of the English throne. As one family gained dominance,

supporters of

the other were often jailed on flimsy charges" (Longman).

Malory was a supporter of the Earl of Warwick, who in the early years of the Wars of the Roses was a Yorkist, opposed to Henry VI and the Lancastrian party. Malory was charged, at various times, with rape, cattle theft, intimidating monks, and other similarly "unknightly" charges; it’s noteworthy that most often they were brought against him by the Lancastrian Duke of Buckingham and his associates, and that Buckingham in fact appointed himself judge and a member of the jury for several of Malory’s trials, which certainly puts the charges into a more partisan light. But Malory was also clapped up in London prisons, from which he seemed to have no trouble escaping repeatedly, and his jailers get into worse and worse trouble because Malory, like Robin Hood, seemed to be able to escape at will, round up a group of supporters, and create more political mayhem. When the Duke of York was named Regent for the temporarily-insane Henry VI in 1460, Malory was given a Yorkist royal pardon—yet a decade later, he is back in jail in London (though he was never put on trial) and specifically excluded from pardons as a die-hard Lancastrian. (Warwick, his overlord, had by this time changed sides to support the Lancastrians and Malory apparently stayed loyal to his lord.)

In October 1470, when the Lancastrians returned to power, "among their first acts was freeing those of their party who were in London prisons. One of the prisoners probably freed was Malory, whom we know had been in Newgate Prison because he signs as witness to several legal documents while there. Six months later, Sir Thomas Malory of Newbold Revel died and was buried under a marble tombstone in Greyfriars, Newgate, which, despite its proximity to one of the jails in which he had been imprisoned, was the most fashionable church in London. On the day of Malory's death, King Edward landed in Yorkshire, and two months later the Yorkists were back in power" (Field 1993: 117). Although "the original tombstone was destroyed, ... its inscription survives in this early sixteenth-century transcript, which calls [Malory] valens miles (‘a valiant knight’) of the parish of Monks Kirby in Warwickshire and says he died on 14 March 1470, which (since the year began on 25 March) is what is now called 1471" ( Field 1993: 126). And so, the ambiguity, contradiction, and paradox which surround the man remain.

Works Cited

Field, P.J.C. "Malory’s Life Records." A Companion to Malory. Ed. Elizabeth Archibald and A.S.G. Edwards. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1996. 115-30.

----------. The Life and Times of Sir Thomas Malory. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1993.

Le Morte

Darthur Notes

Le Morte

Darthur Notes

Sources: Longman Anthology online notes, http://wps.ablongman.com/long_damrosch_britlit_2/0,6737,199713-,00.html ; http://occawlonline.pearsoned.com/bookbind/pubbooks/damrosch_awl/chapter2/medialib/malory.html and Esther Lombardi, "Arthurian Romance," About.com: http://classiclit.about.com/library/weekly/aa012100c.htm

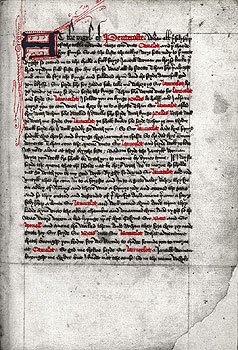

The title, "Le Morte Darthur," is taken from the epilogue of William Caxton's landmark illustrated edition of 1485. The epilogue tells us that "this book was ended the ninth year of the reign of King Edward the Fourth (either 1469 or 1470), by Sir Thomas Maleore (one of the variant spellings of Malory), knight." Until 1934, when a handwritten manuscript of an earlier stage of Malory’s text was discovered at Winchester College (see Richard Altick's The Scholar Adventurers for a funny account of the episode), the version Caxton printed was assumed to be Malory’s own. This "Winchester Manuscript," however, shows that Caxton edited, sometimes condensed, and rearranged Malory’s work to make it into one "hoole booke;" the Winchester text seems to be more of eight tales that connect together. The Winchester Manuscript at some time was in Caxton's print shop, according to analysis of ink traces found on one of its pages, so that even complicates the textual situation more. Now the Winchester Ms. is in the British Library.

Esther Lombardi in an article on About.com says that "During one or more of his imprisonments, Malory composed, translated, and adapted his great rendering of Arthurian material, which is the most complete treatment of the story. The French Vulgate Cycle (1225-1230) served as his primary source, along with the 14th-century English poems The Alliterative Morte d'Arthur and the Stanzaic Morte. (Malory may have had access to the Greyfriar’s Library in London and to several aristocratic libraries in Yorkshire, but where he got some of his sources is still unknown.) Taking these, and possibly other, sources, he disentangled the threads of narration and reintegrated them into his own creation. Part history, part chronicle, part narrative, part sermon, and utterly memorable synthesis of Arthurian myth, his is the version of the Arthurian legend that endures into modern times."

" The

spectacle of a nation threatening to crumble into clan warfare provides much of

the thematic weight of the Morte Darthur, while the declining chivalric

order of the later fifteenth century underlies Malory's increasingly elegiac

tone. The chivalric code was slipping away even in the 14th-century when Chaucer

satirizes it in the Wife of Bath’s Tale. While the Middle Ages still had

promise, it was also a time of great change. Malory must have known that the

ideal of chivalry was dying out. From his perspective, order falls into chaos.

The fall of the Round Table represents the destruction of the feudal social

system, with all its attachments to chivalry" (about.com).

The

spectacle of a nation threatening to crumble into clan warfare provides much of

the thematic weight of the Morte Darthur, while the declining chivalric

order of the later fifteenth century underlies Malory's increasingly elegiac

tone. The chivalric code was slipping away even in the 14th-century when Chaucer

satirizes it in the Wife of Bath’s Tale. While the Middle Ages still had

promise, it was also a time of great change. Malory must have known that the

ideal of chivalry was dying out. From his perspective, order falls into chaos.

The fall of the Round Table represents the destruction of the feudal social

system, with all its attachments to chivalry" (about.com).

"Whether he gained his remarkable knowledge of French and English Arthurian tradition in or out of jail, Malory infused his version of these stories with a darkening perspective very much his own. Malory sensed the high aspirations, especially the bonds of honor and fellowship in battle that held together Arthur's realm. Yet he was also bleakly aware of how tenuous those bonds were and how easily undone by tragically competing pressures. These include the centuries-old Arthurian preoccupation with transgressive love, but Malory is more concerned with the conflicting claims of loyalty to clan or king, the urge to avenge the death of a fellow knight, and the resulting alienation even among the best of knights. Still more unnerving, agents of a virtually unmotivated or unexplained malice have ever more impact as the Morte d'Arthur progresses. His own political experiences in the service of the Earl of Warwick undoubtedly factor into these developments" (about.com). Malory writes in the "Mirror for Magistrates" tradition: a book that is dedicated, in large part, to teaching people who would wield power ("magistrates") how to do so wisely. (Machiavelli's The Prince is another famous book in this tradition.) In a way, the Morte d'Arthur centers on the loss of honor, of loyalty, and of fidelity to a lord--and its consequent costs to political stability. When Gawain calls for vengeance he addresses "my king, my lord, and mine uncle"--a summary of the conflicting codes with which Malory deals.

The author of the About.com article argues that "As a character, Arthur is much weaker than we usually imagine, as he is ultimately unable to control his own knights and the events of his kingdom. Arthur's ethics fall prey to the situation; his anger blinds him; and he is unable to see that the people he loves can and will betray him. Throughout Morte Darthur we notice the Wasteland of characters that cluster together at Camelot. We know the ending (that Camelot must eventually fall into its spiritual Wasteland, that Guenevere will flee with Launcelot, that Arthur will fight Launcelot, leaving the door open for his son Mordred to take over – reminiscent of the Biblical King David and his son Absalom – and that Arthur and Mordred will die, leaving Camelot in turmoil). Nothing–not love, courage, fidelity, faithfulness, or worthiness – can save Camelot, even if this chivalric code could have held up under the pressure. None of the knights are good enough. We see that not even Arthur (or especially Arthur) is not good enough to sustain such an estates ideal in such corrupt times. In the end, Guenevere dies in a nunnery; Launcelot dies shortly thereafter, a holy man."

What

makes the story survive, beyond its narrative claims, is its style. Malory was

the first English writer to make prose as sensitive an instrument of narrative

as English poetry has always been. Read "The Healing of Sir Urry" or Lancelot’s

final farewell to Guinevere before the court and you will see a prose style as

potent and as compact as any you will ever find. If Chaucer is the father of

English verse, then Malory is the father of English prose, as

the Cambridge History of

English Literature contends:

What

makes the story survive, beyond its narrative claims, is its style. Malory was

the first English writer to make prose as sensitive an instrument of narrative

as English poetry has always been. Read "The Healing of Sir Urry" or Lancelot’s

final farewell to Guinevere before the court and you will see a prose style as

potent and as compact as any you will ever find. If Chaucer is the father of

English verse, then Malory is the father of English prose, as

the Cambridge History of

English Literature contends:

"There is a kind of cadence, at times almost musical, which bears the narrative on with a gradual swell and fall proportioned to the importance of the episodes, while brevity, especially at the close of a long incident, sometimes approaches to epigram. But the style fits the subject so perfectly as never to claim attention for itself. A transparent clarity is of its essence. Too straightforward to be archaic, idiomatic with a suavity denied to Caxton, Malory, who reaches one hand to Chaucer and one to Spenser, escaped the stamp of a particular epoch and bequeathed a prose epic to literature."

And it is Malory's version of the story—told musically in Camelot, in animation in The Sword in the Stone, and in revisionist history in King Arthur, First Knight, Monty Python and the Holy Grail and Excalibur, that still continues to resonate with readers and viewers today. It was estimated in the late 1980s that the three lliterary figures about whom the most literary criticism had been written were Christ, Hamlet, and King Arthur—and the fascination endures.