(click here for a PDF version to print out)

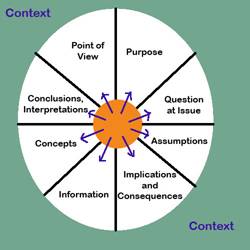

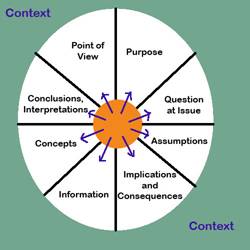

Most of you have learned something about logical fallacies (PHG pp. 37-38 and many other sources). These are traps in making a point that disconnect or misuse the connections between the elements of critical thinking or traps that alter the true question at issue. Sometimes a writer may use these deliberately to try to persuade or mislead an audience, while on other occasions, they may reflect inaccurate or incomplete critical thinking on the writer’s part. In either circumstance, thinking about the ways the elements work together will help you avoid these traps and strengthen the presentation of your thinking. Here are some of the most common fallacies, along with explanations of what kinds of thinking traps cause them.

Begging the Question (or circular logic) happens when the writer presents a claim as information that supports or proves the argument. This error leads to an argument that goes around and around, with evidence making the same claim as the proposition. Because it is much easier to make a claim than to support it, many writers fall into this trap.

Example: "The Patriots are the best team in football because they have the best players. The most talented players in the league want to play for the Patriots because they always win and go to the playoffs. That success comes from the great players they have." The argument continues around in the logical circle because the support assumes that the claim is true rather than proving its truth.

Problems with assumptions and conclusions

Non Sequitur arguments don’t follow a logical sequence. The conclusion doesn’t logically follow the explanation. These fallacies can be found on both the sentence level and the level of the argument itself. Oftentimes there may be a connection in the writer or speaker’s mind, but a number of steps between the first and second statement are not made explicit in the written version, so the audience cannot see the connection that was intended.

Example: "The rain came down so hard that the baseball team lost." Rain and baseball success may have nothing to do with one another. The force of the rain does not affect how the team plays. If other steps were supplied (the slippery field made our players commit errors, etc.), perhaps the sequence would work, but not as stated.

Problems with consequences and conclusions

Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc (after this, therefore also this) arguments, or post hoc for short, assume a faulty causal relationship. One event following another in time does not mean that the first event caused the later event. Writers must be able to prove that one event caused another event and did not simply follow in time. Because the cause is often in question in this fallacy, we sometimes call it a false cause fallacy.

Example: "Staying up all night and cramming before a test helps me get better grades. I did that and got an A on my last test in history." This arguer ignores other possible causes like how much he had studied previously and how easy the test was.

Problems with conclusions

Hasty Generalizations base an argument on insufficient evidence. Writers may draw conclusions too quickly, not considering the whole issue. They may look only at a small group as representative of the whole or may look only at a small piece of the issue.

Example: Concluding that all sorority members are husband-hunting blondes because you know three such women who belong to sororities is a hasty generalization. The evidence is too limited to draw an adequate conclusion.

Problems with information and of conclusions

Sweeping Generalizations make too much out of too little; they imply that what applies to some circumstances must apply to all or that a rule that is generally correct applies in an inappropriate circumstance.

Example: "All fast food is fattening." Watch particularly for overly-inclusive words like all, must, always, etc., which may make statements apply more broadly than you intend them to.

Example: “Conservatives oppose government interference in people’s personal lives, so they must oppose Federal restrictions on abortion, which is one of the most personal decisions a person can make.”

Problems with conclusions and assumptions

False Analogies presume that you can reach a conclusion by comparing one thing to another, even when the comparison is so far-fetched or inapplicable that its relevance is minimal. Because our minds tend to think in comparisons, false analogies are particularly appealing logical traps. Remember that analogies show similarities, but don’t actually prove anything.

Example: “Two of the biggest

commitments in our lives—buying cars and buying houses—demand that we evaluate

the commitment before we make it. So we test drive the car or get house

inspections before we enter into those binding agreements. Likewise, we should

insist that people who want to get married live together before marriage. That

way they can evaluate whether the relationship

will work, and it will reduce the number of divorces by weeding out the

inappropriate pairings before people make a legal commitment to the

relationship.”

Example: "Forcing students to attend cultural events is like herding cattle to slaughter. The students stampede in to the event where they are systematically ‘put to sleep’ by the program." While the analogies in both cases are vivid, the difference between the items compared is so vast that the analogy becomes a fallacy.

Problems with conclusions

Red Herrings have little relevance to the argument at hand. Desperate arguers often try to change the ground of the argument by changing the subject. The new subject may be related to the original argument, but does little to resolve it.

Example: "Winthrop should pave the lot behind Dinkins. Besides, I can never find a parking space on campus anyway." The writer has changed the focus of the argument from paving to the scarcity of parking spaces, two ideas that may be related, but are not the same argument.

Changing the question at issue

Equivocation happens when the writer makes use of a word’s multiple meanings and changes the meanings in the middle of the argument without really telling the audience about the shift. Sometimes this is represented in quibbling over words, as when former President Clinton said in a deposition, “That depends on what you mean by ‘is’.” He was equivocating. This fallacy is sometimes called “false definition.”

Example: When representing himself in court, a defendant said "I have told the truth, and I have always heard that the truth would set me free." In this case, the defendant switches the meaning of truth. In the first instance, he refers to truth as an accurate representation of the events; in the second, he paraphrases a Biblical passage that refers to truth as a religious absolute. While the argument may be catchy and memorable, the shifting definitions fail to support his claim.

Problems with concepts and conclusions

Ignoring the Question is similar to presenting a red herring. Rather than answering the question that has been asked or addressing the issue at hand, the writer shifts focus, supplying an unrelated argument. In this way, the writer dodges the real issues of the debate.

Example: During a public debate, a political candidate is asked a pointed, specific question about some potentially illegal fund-raising activity. Instead of answering the allegations, the candidate’s reply stresses the need to fight terrorism and prevent another 9/11. The response is eloquent and moving but shifts the focus from the issue at hand.

Changes the question at issue

Opposing a Straw Man is a tactic used by a lot of writers because they find it easier to refute a weak spot in the opposition. Writers pick a weak or barely relevant point made by the opposition because it is easier to deal with, and try to make that into the center of the argument. Doing so diverts attention from the real issues and rarely, if ever, leads to resolution or truth.

Example: The debate over banning soft drink machines in schools centers around health issues. Supporters of the drink machines bring up the revenue they generate for the PTO as an important issue. This point has little relevance to the actual health issue but diverts attention to supporting the PTO—a concept that is hard to oppose—and tries to make that the central point in deciding whether the soda machines should stay.

Changes the question at issue and/or purpose

Either—Or arguments reduce complex issues to black and white choices and suggest that there are only two choices when more exist. Most often issues will have a number of choices for resolution. Because writers who use the either-or argument are creating a problem that doesn’t really exist, we sometimes refer to this fallacy as a false dilemma.

Example: "Either we go to Ft. Lauderdale for the whole week of Spring Break, or we don’t go anywhere at all." This rigid argument ignores the possibilities of spending part of the week in Ft. Lauderdale, spending the whole week somewhere else, or any other options.

Problems with alternatives

Slippery Slopes suggest that one step will inevitably lead to more, eventually negative steps. While sometimes the results may be negative, the slippery slope argues that the descent is inevitable and unalterable. Stirring up emotions against the downward slipping, this fallacy can be avoided by providing solid evidence of the eventuality rather than speculation.

Example: "If we force public elementary school pupils to wear uniforms, eventually we will require middle school students to wear uniforms. If we require middle school students to wear uniforms, high school requirements aren’t far off. Eventually even college students who attend state-funded, public universities will be forced to wear uniforms." Such arguments often appeal to people’s fears and hope for a knee-jerk agreement rather than thoughtful consideration.

Problems with consequences

Bandwagon Appeals (ad populum) try to get everyone on board. Writers who use this approach try to convince readers that everyone else believes something, so the reader should also. The fact that a lot of people believe something, of course, does not make it so.

Example: "Carrie is the best singer in the United States; twenty million American Idol fans can’t be wrong!" Of course they can. Winners of such shows are often chosen for their popularity or their aesthetic appeal rather than for having the most meritorious musical talent.

Problems with assumptions and point of view

False Authority is a tactic used by many writers, especially in advertising. An authority in one field may know nothing of another field. Being knowledgeable in one area doesn’t constitute knowledge in other areas.

Example: A popular sports star endorses a particular energy drink. His skill as a player does not qualify him as an expert on nutrition and fluid replacement.

Problems with information and interpretation

Ad Hominem (attacking the character of the opponent) arguments limit themselves not to the issues, but to the opposition itself. Writers who fall into this fallacy attempt to refute the claims of the opposition by bringing the opposition’s character into question.

These arguments ignore the issues and attack the people.

Example: People claim that women aren’t qualified to be President because they’re too likely to be emotional during ‘that time of the month’.

Example: “How dare you tell me to

stop hitting my child! You don’t have any children; you don’t know anything

about disciplining them!”

In both cases, rather than proving the claim, the

arguer makes some personal characteristic of the opposition the question at

issue rather than the issue itself.

Problems with assumptions and point of view

Tu Quoque (you’re another) fallacies avoid the real argument by claiming that the opponent is guilty of the same thing. Like ad hominem arguments, they do little to arrive at conflict resolution. Many times these fallacies can be thought of as arguments that two wrongs make a right.

Example: "How can the police ticket me for speeding? I see cops speeding all the time."

Problems with assumptions and interpretations

Poisoning the Well is a logical booby trap that tempts the audience to fall into the ad hominem fallacy. It makes a false assumption about the opposition even before the argument begins, and thus makes it hard for reasoned critical thinking to take place.

Example: “You can’t really expect the administration to understand the need to expand the African American studies program. They’re successful white academics; they have no idea what real-life obstacles African Americans struggle with or why they need to have a more Afrocentric education.” The speaker poisons the well even before tackling the need to expand the program by trying to convince the audience that the administration members, based on their racial composition and personal backgrounds, are incapable of understanding an argument.

Problems with assumptions and point of view

Composition and Division are two sides of the same fallacy, which sets up a false relationship between the parts and the whole. Composition assumes that what applies to the parts applies to the whole, and division assumes that what applies to the whole also applies to the parts. Sometimes these assumptions are valid; sometimes they’re not.

Example of Composition: “I

don’t understand why this casserole tastes so lousy. I

used the most expensive ingredients in the store.” Just because you used the

best parts doesn’t mean that the whole will turn out as expected.

Example of Division: “Carolina has the third best defense in the league, so it’s not fair that only one of their defensive players was selected to the Pro Bowl.” Teamwork rather than individual stars may be the reason why the whole defense excels, where Pro Bowl selections honor individual accomplishments.

Problems with assumptions and conclusions

The Genetic Fallacy assumes that the original source of an idea or symbol is a sound basis for evaluating its truth or reasonableness. It has nothing to do with the idea’s truth or applicability; rather, it looks only at the idea’s origin (hence the term ‘genetic’).

Example: “The swastika has been seen in native people’s art for over 3000 years. It shows up in India, in ancient Troy, and in Native American artifacts. There’s nothing wrong with displaying this ancient cultural symbol.” This genetic argument ignores all the misuses of the swastika in recent history and assumes that its innocent origins outweigh all intervening historical baggage.

Problems with assumptions and concepts (could also be changing the question at issue)

Appeal to ignorance is the claim that a belief must be true because there is no evidence to disprove the thesis. That is, the absence of negative evidence means that the positive must be true.

Example: “The Loch Ness Monster is just a myth. If there were a large aquatic creature in the lake, we would have evidence of it by now.” Because the arguer knows of no physical evidence to prove Nessie’s existence, she assumes that the Monster cannot exist.

Problems with assumptions and information

Appeal to authority assumes that something is true just because someone (or something) the speaker respects holds that opinion; thus, other proof is not needed.

Example: “The Bible says it; that settles it.” or “Oprah said that chocolate cures cancer, so if I eat chocolate every day I won’t get cancer.” In both cases, the arguer’s respect for or belief in the source of his information is substituted for actual proof that the claim is true.

Problems with assumptions and conclusions

The appeal to fear uses a threat to the audience as a persuasive weapon. Whether or not the statement is true, the actual or implied threat makes the audience give way to the speaker’s wishes.

Example: “The government has to have the power to secretly wiretap individual citizens’ conversations, or it won’t be able to stop another 9/11 from happening.” Statements like these play on the audience’s fears of potential consequences to cover up the lack of proof that such powers are the only way of preventing disaster.

Problems with implications and consequences

This handout adapts material from the Winthrop Writing Center's handout on logical fallacies.