ENGL 622: Eikonoklastes Handout

Barbara Lewalski,

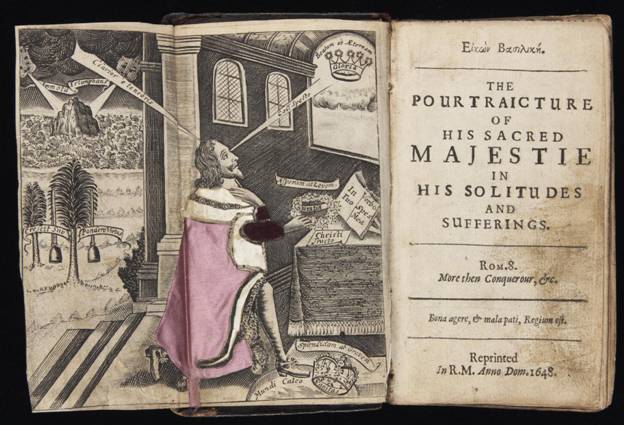

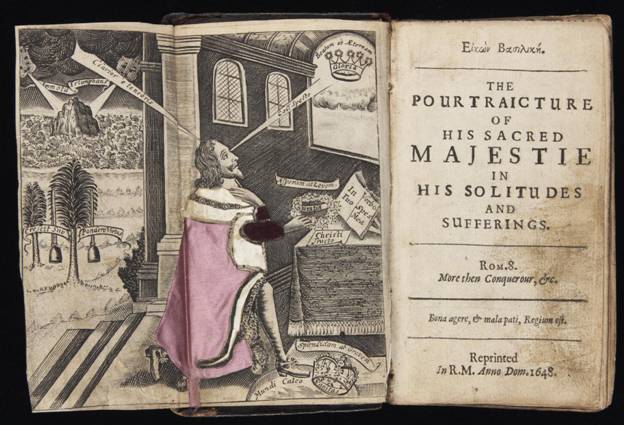

The Life of John Milton 265: The

frontispiece by William Marshall shows “Charles kneeling in prayer and grasping

a crown of thorns (inscribed Gratia),

with his regal crown at his feet (inscribed

Vanitas) and a crown of gold awaiting

him above (inscribed Gloria); in the

emblematic landscape, a palm tree hung with weights and a rock blasted by

tempests represent the king’s virtue strengthened by trial. Marshall’s portrait

of Charles contrasts sharply with his unflattering engraving of Milton in the

1645 Poems, reinforcing the suspicion

that the Milton portrait was intended as satire. The Marshall engraving prepares

for the image or icon of the king conveyed in the text: a second David, deeply

religious in his psalm-like prayers; a misunderstood monarch innocent of any

deliberate wrongdoing, who always intended the best for the English people, a

loving father to his children and his subjects; a defeated king negotiating

honorably with his captors; a man of high culture, mildness, restraint,

moderation, and peace persecuted by vulgar and blood-thirsty enemies; and now a

martyr for conscience in refusing to compromise on bishops and liturgy and his

ancient prerogatives. Like the frontispiece engraving the text also identifies

him as a second Christ in his sufferings and in his gestures of forgiving his

enemies. Charles regrets that he was sold by the Scots to parliament at a higher

rate than Christ by Judas; he likens his negotiations with parliament to Christ

tempted by Satan; and he begs God to forgive the English people in Christ’s

words, ‘they know not what they do.’ The pathos and sentiment, the simple,

earnest language in which Charles defends his actions, the fiction that this

text contains the king’s private reflections and meditations rather than polemic

argument, and the construction of this book as deathbed testimony—now heard from

the grave—produced a nearly irresistible rhetorical effect.”

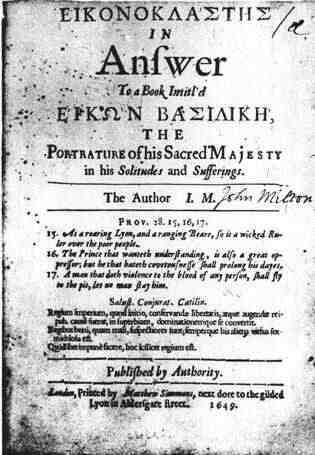

Here is Milton’s title page:

Link to oaths of supremacy and allegiance (see page 1092, right bottom):

http://www.lukehistory.com/resources/oaths.html

Chapter 13: “Upon the calling of the Scots, and their coming”

Indeed, if the race of kings were eminently the best of men, as the breed at Tutbury is of horses, it would in reason then be their part only to command, ours always to obey. But kings by generation no way excelling others, and most commonly not being the wisest or the worthiest by far of whom they claim to have the governing; that we should yield them subjection to our own ruin, or hold of them the right of our common safety, and our natural freedom by mere gift, (as when the conduit pisses wine at coronations,) from the superfluity of their royal grace and beneficence, we may be sure was never the intent of God, whose ways are just and equal; never the intent of nature, whose works are also regular; never of any people not wholly barbarous, whom prudence, or no more but human sense, would have better guided when they first created kings, than so to nullify and tread to dirt the rest of mankind, by exalting one person and his lineage without other merit looked after, but the mere contingency of a begetting, into an absolute and unaccountable dominion over them and their posterity.

Chapter 6, “Upon his Retirement from Westminster”

The simile

wherewith he begins I was about to have found fault with, as in a garb somewhat

more poetical than for a statist: but meeting with many strains of like dress in

other of his essays, and hearing him reported a more diligent reader of poets

than politicians, I begun to think that the whole book might perhaps be intended

a piece of poetry. The words are good, the fiction smooth and cleanly; there

wanted only rhyme, and that, they say, is bestowed upon it lately.

Chapter 19: “Upon the Nineteen Propositions, &c.”

So that the parliament, it seems, is but a female, and without his procreative reason, the laws which they can produce are but wind-eggs: wisdom, it seems, to a king is natural, to a parliament not natural, but by conjunction with the king; yet he professes to hold his kingly right by law; and if no law could be made but by the great council of a nation, which we now term a parliament, then certainly it was a parliament that first created kings; and not only made laws before a king was in being, but those laws especially whereby he holds his crown. He ought then to have so thought of a parliament, if he count it not male, as of his mother, which to civil being created both him and the royalty he wore. And if it hath been anciently interpreted the presaging sign of a future tyrant, but to dream of copulation with his mother, what can it be less than actual tyranny to affirm waking, that the parliament, which is his mother, can neither conceive or bring forth “any authoritative act” without his masculine coition? Nay, that his reason is as celestial and life-giving to the parliament, as the sun’s influence is to the earth: what other notions but these, or such like, could swell up Caligula to think himself a god?